Byzantine Art and Architecture

First Things First...

A unit on Byzantine art allows for an engaging examination of the monumental transition from the peak artistic production of the Roman Empire to the great artistic commissions of the Middle Ages. Beginning with Constantine the Great’s creation of the new capital of Byzantium shortly before his death in 337 CE, this lesson traces the evolution of Byzantine art from its Early Christian explorations through its peak years of artistic and architectural production, and finally to its eventual decline. This period spans roughly from 527 to 1453 CE.

Background Readings

Content Suggestions

In an hour and fifteen minute class period, you could discuss the following images:

- Colossal Constantine the Great, originally Basilica Nova, 315–30 CE

- Good Shepherd, Orants, and Story of Jonah, Catacombs of Saints Peter and Marcellinus, earth fourth century CE

- Anthemius of Tralles and Isidorus of Miletus, Hagia Sophia, 523–37 CE

- Transfiguration of Christ, Church of Virgin, Monastery of Saint Catherine, Mount Sinai, c. 548–65

- Basilica of San Vitale, Ravenna, Italy, 526–47 CE

- Emperor Justinian and His Attendants, San Vitale, c. 547 CE

- Empress Theodora and Her Attendants, San Vitale, c. 547 CE

- Page from the Chludov Psalter, ninth century CE

- Interior, Cathedral of Saint Mark, Venice, begun 1063 CE

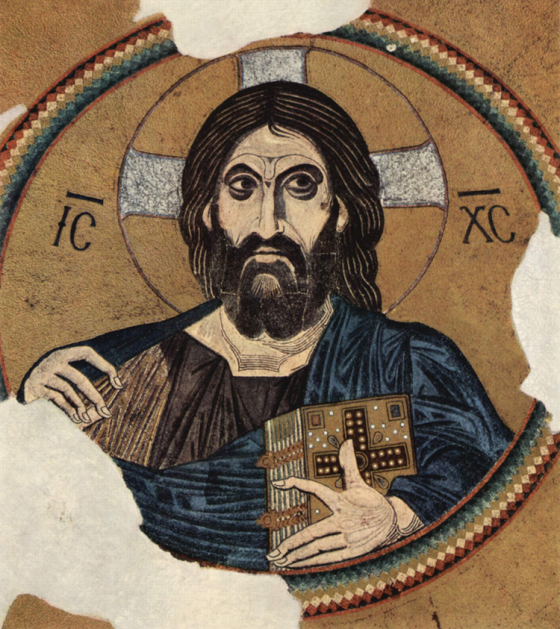

- Christ Pantocrator, Central Dome, Church of the Dormition, Daphni, Greece, c. 1080–1100 CE

- Funerary Chapel, Church of the Monastery of Christ in Chora, Istanbul, Turkey, c. 1315–21 CE

- Anastasis, Funerary Chapel, Church of the Monastery of Christ in Chora, Istanbul, Turkey, c. 1315–21 CE

General Concepts

These images have been selected not only to represent a strong survey of Byzantine artistic production but also to reflect several key themes, including:

- the transition from ancient Roman artistic production to a uniquely Byzantine style in service of the Church/religious doctrine.

- the negotiation between the classical Roman conventions of the figure and the Byzantine shift toward abstraction/stylization of the figure.

- the role of pattern, texture, and visual opulence in Byzantine art and the increased popularity of the mosaic medium.

- artistic and architectural commissions that reinforce patron’s wealth and power.

Glossary:

Good Shepherd imagery: syncretic depictions of a Christ-like figure that merged pagan figural styles with Early Christian meaning.

Iconoclasm: literally translates as “image breaking”; a period of the destruction of religious imagery for fear of idolatry.

Mandorla: an almond-shaped enclosure encircling depictions of Christ.

Mosaic: patterns or pictures made by embedding small pieces (tesserae) of stone or glass in cement on surfaces such as walls and floors.

Orants: figural depictions of worshippers, denoted by their raised, outstretched arms.

Syncretism: the melding of different artistic traditions or conventions to create new meaning.

Introduce your session on Byzantine art by providing some preceding context, such as the emergence of Byzantine culture from the Roman Emperor Constantine the Great (use the Colossal Statue of Constantine the Great for visual reference). Constantine’s reform, in the form of the Edict of Milan in 313 CE, established Christianity as the state’s official religion. Previously, it had functioned as an underground cultic form of worship. This Colossal Statue allows a general visual image of Constantine but it also reflects a concluding moment of ancient Roman artistic production. This monumental sculpture once prominently stood in the Basilica Nova, also known as the Basilica of Maxentius (c. 312 CE), completed during Constantine’s reign. This Basilica Nova was erected in the heart of the ancient Roman Forum and took on the function of a law court. The structure’s architectural footprint of the basilica would eventually become the basic template for future Christian churches.

Before such elaborate structures could be built, however, Christians had, for generations, transformed clandestine spaces with devotional visual imagery. An example of one of these secluded sites of early Christian worship can be found in Rome’s Catacomb of Saints Peter and Marcellinus, which has imagery painted in its cubiculum, or small rooms, such as a fourth-century painting of the Good Shepherd, Orants, and Story of Jonah. This scene reveals the potential of syncretism, wherein early Christians borrowed prevalent or popular imagery from earlier cultures and translated it into new images with Christian messages. The central figure of the Good Shepherd, for example, recalls classical Greek sculpture, yet here it is intended to allude to a comforting image of Christ who also serves as shepherd. The idea behind such quotations was not just to ground Christianity in a historical lineage, but also to incorporate figural types that Christian converts found familiar. Around this central figure of the Good Shepherd are orants, or worshipers, and semi-circular lunettes that recount the story of Jonah. This old testament story was a popular narrative among early Christians since it foreshadowed Christ’s life and eventual resurrection.

Constantine’s reforms also included his selection of Byzantium as his new capital city, which he renamed “Constantinople” in 330 BCE (now the city of Istanbul in present-day Turkey). Shifting the Roman Empire’s center of control to the east, artistic representations moved away from the classical style of ancient Rome. Instead of pagan images of deities from the Roman pantheon and a classical treatment of the figure, Byzantine art stressed religious devotion and transcendental qualities. In the Byzantine era, artists strove for imagery that seemingly reflected an otherworldly or divine existence and architecture that encouraged religious enlightenment.

The Early Byzantine Period (527–726 CE) was ushered in with the reign of Emperor Justinian I, also known as Justinian the Great–both for his drive to recapture lost territories across the Mediterranean and for his monumental patronage of art and architecture. Justinian’s commissions exemplify the stylistic treatment characteristic of early Byzantine art. One of his most significant architectural commissions was for the Church of the Hagia Sophia. Translated as “Holy Wisdom,” the Hagia Sophia was originally built and dedicated in the fourth century and served as the cathedral, or bishop’s seat, for Constantinople. From its dedication in 360 CE to the Nika Revolt of 532 CE, which proved to be the most violent week of rioting in city’s history, the Hagia Sophia was destroyed twice and rebuilt once, reflecting the symbolic power this religious structure held in its relation not only to Christianity but also to the city of Constantinople.

One of Justinian I’s first building campaigns following the Nika Revolt was to rebuild this cathedral. He turned to scholars Anthemius of Tralles and Isidorus of Miletus to design a revolutionary new church, one that adopted a central plan with extensions to the west and east by half dome apses. The dramatically raised, soaring central dome seems to magically float on light, creating a visually spectacular interior that originally had vibrant mosaic work. Unfortunately much of the original mosaic work has been destroyed.

Earthquakes in the sixth and ninth centuries, and the period of Byzantine Iconoclasm beginning around 726 CE, significantly damaged the structure and decoration of the Hagia Sophia. In its conversion to a mosque in 1453, when the Ottoman Empire overtook Constantinople, the religious work experienced more degradation, as mosque workers were known to sell individual mosaic tesserae as good luck charms for those who visited the space. Thus, we are left to imagine what the visual impact of this interior would have looked like.

A suggestion, however, of this visual splendor can be seen in a ninth or tenth-century mosaic added to the Hagia Sophia following the end of the iconoclastic age. Known as the Imperial Gate Mosaic as it adorns the entrance to the church reserved for the Emperor, this magnificently luminous mosaic reveals Christ at the center, flanked by roundel portraits of the Angel Gabriel to his left and Mary to his right. At Christ’s feet appears a kneeling figure of, most likely, Emperor Leo VI, also known as Leo the Wise. His image at the feet of Christ was intended to serve as an eternal reminder that even the most powerful Emperor was humbled in the presence of Christ.

To get a further sense of how visually stimulating this interior once was, one can also look to the Transfiguration of Christ from the Church of the Virgin at Mount Sinai’s Monastery of Saint Catherine (549–64 CE). Here, the figure of Christ towers over the center of the apse, his significance reinforced by his almond-shaped mandorla rendered in varying shades of blue. Rays of light extend from his body beyond the mandorla into the brilliant gold ground of the mosaic, reaching the figures that surround him. At the far left and right, Elijiah (left) and Moses (right) flank Christ, while John, Peter, and James (from left to right) appear directly below Christ appear. Enclosing this scene is a series of medallion or roundel portraits of additional apostles and prophets. While the treatment of these figures alludes to the classical Roman past with their toga-like robes and hint of contrapposto in their stances, the mono-dimensional treatment of the figures, combined with the lavish vibrancy of color, creates an almost supernatural feel to this mosaic that characterizes the Byzantine style.

A similar sensation is achieved at Ravenna’s Church of San Vitale. where the interior is also filled with exceptional mosaic work. In addition to a spectacular rendition of Christ Enthroned in the chancel, two monumental mosaics, one depicting Emperor Justinian and His Attendants and the other illustrating the Empress Theodora and Her Attendants, flank either side of the apse. Both mosaics commemorate Justinian and Theodora as eternal patrons of the church (even if they may have never actually visited!). Justinian, clothed in an imperial purple cloak and porting a bejeweled crown, holds a gold paten, representing the Host. On his right appears Maximianus, the archbishop of Ravenna. These two central figures are surrounded by various officials from the church who hold various liturgical objects, as well as a group of soldiers on the far right, their shields emblazoned with the chi rho symbol of early Christianity. Theodora, on the opposite wall, appears similarly bejeweled and extends an elaborate chalice, adopting a pose that mimics the scene of the Magi embroidered along her cloak’s hem.

Just as in the Transfiguration of Christ, both mosaics of the Emperor and his wife ascribe to the flattened aesthetic of Byzantine artistic production. An emphasis on depth and perspective is here replaced with flattened, almost floating figures imbued with a brilliant luster. This compositional flattening is perhaps most pronounced in the depiction of the Empress Theodora: while great attention was paid to incorporating complex background elements, such as the parting curtain revealing a doorway to the left of the mosaic or the shell niche above Theodora’s image, they nevertheless do not convey a sense of depth. By flattening the figures along with the picture plane, these compositions transform into very direct imagery that, when combined with the mosaic medium, create a timeless commemoration of the Emperor and Empress in the Church of San Vitale.

Around 726 CE, a period of iconoclasm brought the majority of Byzantine artistic production to a halt. Literally translated as “image breaking,” iconoclasm involved the destruction or desecration of religious imagery for the sake of preventing idolatry, as illustrated in a ninth-century drawing from the Chudlov Psalter. This moment was spurred by ongoing religious debate regarding the function and appropriateness of religious imagery. Those who argued against the use of images feared that worshipers would became too engrossed in the image itself, worshiping the image as an idol rather than focusing on the religious narrative or figures it represents. This controversial issue came to a head under Emperor Leo III, who prohibited the creation of new religious imagery and called for the removal and destruction of extant imagery. During this period, the only acceptable imagery to be included in church interiors was the cross. Following this iconoclastic outbreak, the Middle Byzantine Period (843–1204 CE) began when Empress Theodora reinstated the practice of venerating icons, thereby ushering in a new generation of artistic and architectural production.

The return of the splendor of Byzantine interior decoration can be seen in the Saint Mark’s Cathedral, Venice. Expanding the footprint of the Hagia Sophia to take on a Greek cross shape, Saint Mark’s Cathedral includes five monumental domes, each replete with golden mosaic work (on which work continued until the seventeenth century). While the imagery is no less lavish than earlier examples, imagery has been simplified (e.g., the removal of many superfluous details) since at this point, artists sought to emphasize the primacy of the religious narrative or figure being portrayed.

This is illustrated in a relatively contemporaneous version of Christ Pantocrator in the Church of the Dormition, Daphni, Greece (c. 1080–1100 CE). Located in the central dome of the church, this Christ Pantocrator looms large over worshipers. Holding the New Testament in his left arm and assuming a gesture of blessing with his right, Christ here assumes the traditional posture as Pantocrator, or “ruler of all,” a conventional representation of Christ that became popular during this era.

The invasion of The Fourth Crusade around 1204 brought the Middle Byzantine period to a close. Sacking the city of Constantinople, the crusaders relinquished the vast majority of treasures and relics housed in Byzantine churches (many of these objects were sent to Venice and became part of the collection of the Treasury of Saint Mark’s Cathedral). It was not until Byzantine control was reestablished in 1261 that the Late Byzantine Period (1261–1453 CE) began.

The visual arts of this period reflect a renewed vivacity of visual imagery. A fantastic example is seen in the Anastasis, or Resurrection, in the main apse of the funerary chapel of the Church of the Monastery of Christ in Chora (c. 1310–20 CE). Here the central figure of Christ seems caught mid-stride, his draped fabric animated as if caught up with his movement, and his mandorla behind him tipping to one side. He stands prominently on top of the shackled body of the Devil and the smashed gates to Hell, smashed locks and chains littering the foreground. Having triumphed over evil, Christ pulls the aged figures of Adam and Eve from their sarcophagi. The sense of motion that pervades the entirety of the scene, from the swooping drapery of Christ’s robes to the sensation of motion created in the bodies of Adam and Eve reflect a return to previous Byzantine artistic conventions tempered with a refreshed dynamism of movement.