Globalism and Transnationalism

First Things First...

Globalization and transnationalism are often perceived as phenomena that have had their most apparent impact on art in the contemporary era. Several scholars such as Andreas Huyssen, however, have accurately and persuasively discussed globalization and transnationalism as historically relevant and pervasive topics that contest the belief that cultures can be or were ever actually “pure.”

Instead, cultures/nations/ethnicities/groups have always inevitably interacted, collided, and blended throughout time. In conjunction with this lecture, you might consider today’s digital advancements and increasingly post-neoliberal world from the historical perspective of the Industrial Revolution and the subsequent World Fairs of the late nineteenth and early twentieth century.

Background Readings

Content Suggestions

The key ideas of this lecture can be explored in an hour and fifteen minutes through a variety of examples, including:

- William Marlow, View of the Wilderness at Kew, 1763

- Édouard Manet, Portrait of Émile Zola, 1868

- Jean-Léon Gerôme, The Snake Charmer, c. 1870

- Pablo Picasso, Les Demoiselles D’Avignon, 1907

- Aaron Douglas, Negro in an African Setting from Aspects of Negro Life, 1934

- Zhang Hongtu, Long Live Chairman Mao Series, 1989

- Alighiero e Boetti, Mappa del Mondo, 1989

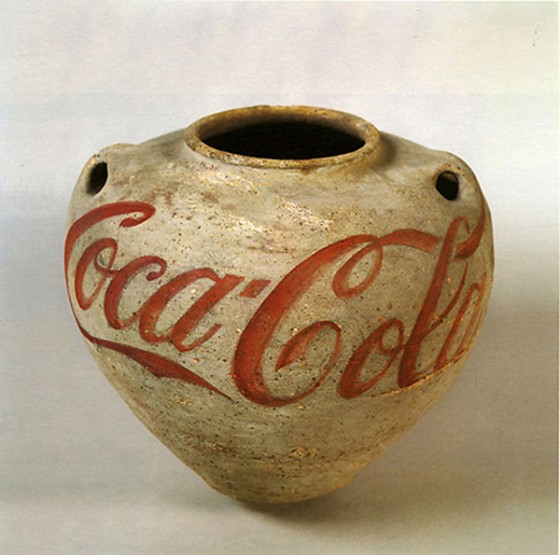

- Ai Wei Wei, Han Dynasty Urn with Coca-Cola Label, 1994

- Yinka Shonibare, The Swing (After Fragonard), 2001

- O Zhang, Daddy and I No. 18, 2006

- Shelly Jyoti, An Ode to Neel Darpan, 2009

- Samson Young, Liquid Borders, 2012

- Laura Kina, Okinawa — All American Food, 2013

Glossary:

Diaspora: This term refers to the dispersal of a particular group of people from their homeland (see “Homeland”, below). Most specifically, it refers to the expelling of the Jews from their homeland, but has been co-opted by many other disciplines to refer to forced, or sometimes voluntary, migrations due to war, poverty, famine, or other traumatic circumstances.

Globalization: Globalization refers to increasing integration of different areas of the world and their respective worldviews, commercial products, ideas, money, and cultural productions. Inherent in this definition is the economic impact of changing borders and definitions of the nation-state (see “Nation-state”, below). In 2000, the International Monetary Fund defined four aspects that comprise globalization: trade and transactions, capital and investment movements, migration and movement of people, and exchange of knowledge. These increasing exchanges are fueled by advancements in transportation and telecommunications. Globalization is sometimes defined as primarily the economic side of transnationalism.

Homeland: the original (usually ethnic and cultural) nation-state and geographic land of a particular group of people.

Nation: people with a common identity that ideally includes shared culture, language, and feelings of belonging.

Nation-State: The modern nation-state generally emerged from the World War II era. Characteristic of the modern world, the concept of nation-states refers to particular types of states in which governments have sovereign power within defined territorial areas (hint: boundaries play a big role!), with populations that are made up of “citizens” who know themselves to be members of their nation-state. Members of nation-states maintain some political sovereignty over the land that is claimed to belong to a nation-state.

Transnationalism: Transnationalism refers to the movement of people, cultures, and ideas across borders and groups. Stemming from the concept of the nation-state (see below), transnationalism also refers to phenomena evident in flows of people, products, and knowledge from one nation to another. These flows are often difficult to define, unstable, and fluid by their very nature.

To get started, William Marlow is a wonderful example of an early world traveler who was interested in other cultures, and more specifically, interested in bringing aesthetics from “exotic” places back to Europe. The Metropolitan Museum of Art’s website offers this description of Marlow’s watercolor View of the Wilderness at Kew: “The magnificent Chinese Pagoda of Kew Gardens, designed in 1757 by William Chambers, has always attracted much attention. In the mid-eighteenth century, the pagoda fueled a rage for such buildings throughout Europe, and even today remains one of London’s main tourist attractions. This sheet forms part of an album with delicately rendered watercolor drawings made by William Marlow after Chambers’s designs, later published as Plans, Elevations, Sections and Perspective Views of the Gardens and Buildings of Kew in Surrey, the Seat of Her Royal Highness, the Princess Dowager of Wales (London, 1783). In addition to this general view, there are three other detailed and architecturally precise drawings of the pagoda, showing its design, construction, and decoration. At a time when a general vogue for chinoiserie was based on imaginative visions of the Orient rather than accurate information, Chambers, who visited China in the 1740s, was able to create stylistically accurate, authentic Chinese designs.”

Édouard Manet’s Portrait of Émile Zola exhibits the contemporaneous French zeal for Japanese aesthetics that would revolutionize French painting, especially in terms of perspective and color. Zola, a writer and contemporary of Manet, was an early defender of painters working outside of the constraints of the Academy. Manet’s portrait of Zola includes the writer sitting in Manet’s studio surrounded by objects that represent him. Hanging on the wall is a reproduction of Manet’s Olympia (1863), the artist’s most controversial work to date, which Zola ardently defended and held to be Manet’s best work. Behind Olympia is an engraving of Diego Velázquez’s The Triumph of Bacchus (1628–9). Both painter and writer highly admired Spanish aesthetics. Finally, a print of the famous Japanese wrestler Utagawa Kuniaki II and a Japanese print screen demonstrate the contemporary trend of Japonisme that helped shift French understanding of perspective and color.

The painting that launched Edward Said’s highly regarded analysis of postcolonialism and Orientalism, Jean-Léon Gérôme’s The Snake Charmer is a well-known example of European perspectives of an exotic and unknown land. Painted in almost photorealistic detail, the painting suggests absolute authenticity in its depiction of a Middle Eastern scene of slumped men watching a nude snake charmer. The painting’s depiction of decrepit locals and glittering ornament as well as its sexualization of the young snake charmer have led critics, including Said, to see Gerôme’s work as an extreme exploitation of a land unknown to his Western audience, whose ideas and beliefs about the Middle East were formed more by stereotypes and fantasies than reality. (Gerôme himself had visited Egypt for the first time in 1856.) This painting is useful for discussing not just colonialism itself, but also the effects of a Western imaginary on colonial states and colonized peoples.

Aside from marking a seminal break from traditional perspectives and introducing a more complete formalistic Cubism, Pablo Picasso’s Les Demoiselles D’Avignon significantly exhibits the artist’s interest in African masks and other materials imported into France at the time due to colonial expansion into Africa. As interest in African cultures grew, so did ethnographic institutions that displayed masks and other artifacts brought back by French settlers. Picasso’s interest in African aesthetics was sparked while viewing some of these masks at an ethnographic museum in Paris. The treatment of the two figures on the left of the painting, especially in their faces, is clearly influenced by the aesthetics of African masks. Scholars have questioned to what extent Picasso would have understood the symbolism and ritual uses of these masks, and to what extent his work was merely formal borrowing meant to subvert Western academic standards.

Negro in an African Setting, one of four panels in Aaron Douglas’s mural series Aspects of Negro Life is an example of what the artist called “Egyptian form,” which featured figures in profile with front-facing eyes like those seen in ancient Egyptian painting. The entire series is highly cinematic and features the same aesthetic style, which is primarily monochromatic with translucent colors and geometric edges. Douglas was a member of the Harlem Renaissance and, like many of his fellow artists, authors, poets, and musicians, was particularly interested in the history of African-Americans, Africans, and Africa itself. The subject of slavery—one sometimes addressed by artists like Douglas—is particularly interesting in the context of globalization and transnationalism. Globalization is defined by the economic channels of trade and exchange of objects and ideas; by definition, slavery is one of the earliest negative products of globalization, and its consequences continue to this day.

Born in 1943, Zhang Hongtu is one of many diasporic Asian artists based in New York City. He was born in China and came to the United States in 1980. His Long Live Chairman Mao series is considered one of Zhang’s first political Pop works where, with just a few simple brushstrokes, he converted the iconic Western face of the Quaker Oats man into the iconic Chinese face of Mao Zedong. As a child of the Communist Revolution in China, Zhang understood the political power of images that could be used to propagandize for political movements and ideas. The cross-pollination of American and Chinese iconography highlighted by Hongtu speaks to the capitalistic agenda that China holds despite its Communist proclamations and can be read as a statement critical of Chinese hypocrisy. However, in Long Live Chairman Mao, Hongtu replaced a benevolent figure of American consumerism with the face of a seemingly benevolent Chinese leader, potentially also revealing the artist’s homesickness for his homeland. Conflicting interpretations are at the heart of this artist’s work, which negotiates the constantly shifting experiences and emotions of transnational (and transplanted) individuals.

Alighiero e Boetti was an Italian artist who exhibited within the Arte Povera movement. He is well-known for incorporating everyday objects into his work as both tools and mediums. In each of the works in his Mappa del Mondo series (known as Mappe), the artist traced a world map onto canvas and colored each country according to its national flag. Each canvas was then delivered to Afghan craftswomen who used it as the model for a tapestry. The first such project was delivered for production by Boetti on a 1971 trip to Afghanistan. For over twenty years, Boetti created over 150 different maps in this manner, which together illustrate shifting world politics and moving borders. Significantly, in the 1980s, Boetti changed from the Mercator map projection to the Robinson projection. The Robinson Projection translates the globe into a flat surface that more accurately reflects the actual size of land masses in relation to one another. The Mercator projection is a more widely used map which sizes land masses according to their historical importance to mapmakers. Alighiero e Boetti’s shift, then, must be seen as a political stance rejecting the Mercator’s unscientific prioritizing of certain places.

For a simple-looking object, Ai Wei Wei’s Han Dynasty Urn with Coca-Cola Label is a highly complicated site of contestation. One of China’s most famous artists, Ai Wei Wei is primarily known for his political dissent toward the Chinese government. Here, he has taken an urn (one of many) that he claims is from the Han Dynasty (206 BCE–220 CE) and emblazoned it with an iconic Western commercial logo. At face value, the work is a palimpsest of eras and cultures mashed together. However, the work also evokes multiple questions and issues. First, is it problematic that an artist has taken a unique antique object and essentially defaced it? On the other hand, Ai Wei Wei’s commentary on the destruction of Chinese culture by the means of commercialism and capitalism can be read as a meta-critique of Chinese authorities, whose banishment of free expression has already destroyed centuries of a Chinese culture once renowned for its poetry, aesthetics, and literature. These issues were further complicated in early 2014 when an individual in Florida destroyed a similar vase that Ai Wei Wei was exhibiting, questioning why this international artist was getting exhibition space and time in a Florida museum rather than a local artist. Horrified, the press stated that an artist had destroyed a one-million-dollar object, but what was actually being destroyed? The original Han Dynasty vase, or the work of a famous international artist? How might we respond to either act? Ai Wei Wei himself destroyed Han Dynasty vases in a series of photographs (Dropping a Han Dynasty Urn, 1995/2009), which was mimicked in 2012 by Swiss artist Manuel Salvisberg’s Fragments of History, which documented prominent collector Uli Sigg dropping a similar Ai Wei Wei work that he owned. The layers of this work are ripe for discussion and present multiple points for potential essays or response papers. For an in-depth consideration, one could read Chin-Chin Yap’s essay “Devastating History” in ArtAsiaPacific.

Yinka Shonibare, who was born in London and grew up in the UK and Nigeria, has described himself as “a postcolonial hybrid.” The Swing (After Fragonard) is an installation based on Jean-Honoré Fragonard’s iconic Rococo painting The Swing (1767), depicting a young girl playing flirtatiously in a garden containing two men. Fragonard paints the young woman as her shoe flies off her foot in a moment of abandon, while a titillated suitor looks on and encourages her. Shonibare’s work preserves the girl, her shoe, and the swing but omits the two men. Her figure is headless, perhaps referencing the guillotine of the French Revolution, which was impending at the time of the original painting, though amputation is also a signature of Shonibare’s work. The artist often removes a limb or a body part from his figures, introducing a disturbing and jolting element to otherwise exquisitely and seamlessly constructed objects.

Shonibare’s figure is likely not a young European woman like Fragonard’s young girl; her skin is darker. He has eschewed the frills and lace of the original girl’s pink gown and instead dressed his figure in vibrant batik fabric, characteristic of his other sculptures and paintings. Batik fabric itself has highly postcolonial characteristics and signifies the Western imagination of African identity by its completely “fabricated” African origin. Indeed, these textiles are also known as Dutch wax textiles, having been appropriated and then mass-industrialized from African designs by the Dutch during the colonial period. Later, English manufacturers copied the Dutch fabrics, using a predominantly Asian workforce to reproduce designs that were originally derived from African textiles, further complicating their chain of production. The fabrics were finally exported to West Africa, where they became popular during several African independence movements. Their bright colors and bold patterns became iconic of a struggle for political and cultural independence. Today they continue to be sold in Africa, but also New York and London, and are often adapted by high-end fashion designers who themselves are highly globalized.

Like Zhang Hongtu, O Zhang (born Zhang Ou) is a Chinese artist based in New York City. She grew up in the outskirts of Guangzhou where her family lived due to persecution during the Chinese Cultural Revolution. Zhang is primarily known for her photographs of a new, emerging generation of Chinese youth who are representative of an increasingly capitalistic China. Her photographic series Daddy and I focuses on Chinese girls who have been adopted by American families, primarily during the period of China’s one-child policy, then after 1991 when it loosened its adoption rules. Since then, over 55,000 Chinese girls have been adopted by American parents, creating multiracial families that have changed the archetype of the traditional American nuclear family. Zhang’s project examines the bond between father and daughter despite or because of their different ethnicities and considers the unique interplay between skin color, ethnicity, and upbringing. She also considers gender issues, as the American concept of “Daddy’s girl” is a component of father/daughter relationships that does not necessarily play a significant role in Chinese society.

Shelly Jyoti, an artist based in Baroda, India who primarily works in textiles created a project called Indigo Narratives to trace the significance of indigo as a transnational and exploitative material. In the 1600s, indigo was brought to Bhuj, India, where colonial interest in the vibrant blue led to so much exploitation that—centuries later—Mahatma Gandhi intervened. To give form to her sculptural textiles, Jyoti traveled to contemporary Bhuj in 2009 to work with ninth-generation Azrak artisans and indigo masters. These artisans are descendants of migrants and represent a history of interchange between different communities. In An Ode to Neel Darpan, Jyoti conceptualized the literary play Neel Darpan in one panel of three that comprise a triptych. Hawks represent British colonizers who twist and manipulate lotuses in their beaks. The lotuses signify planters, British and Indian individuals who acted as intercessors and translators between the British colonizers and the indigo farmers, who are here represented as the hardworking and underappreciated worms. The artist likens Neel Darpan to Harriet Beecher Stowe’s Uncle Tom’s Cabin, which was published in the United States in 1852, just a few years earlier than Neel Darpan. Jyoti’s work highlights the impact of migrations evoked by the spatial movements of artisans from Sindh and Baluchistan to Bhuj, the movement of British missionaries, the return of Gandhi to India from South Africa, and finally the artist’s own movement from Baroda to Bhuj to complete her project.

Samson Young, a young artist based in Hong Kong, is a classically trained musician and composer who creates multimedia projects using contemporary communication technologies. For Liquid Borders, the artist traces, in a sonic fashion, the border between Hong Kong and mainland China. The two are physically separated by both a wall of wired fencing and water. The areas south of the border are restricted and entry without an official permit is forbidden. Over the course of two years, after some of them were opened up, the artist visited zones along the border, collecting sounds that suggest the audio divide between the two spaces. Over time, the artist assembled a body of recordings that he then rearranged into sound compositions and transcribed into graphical notations. The project is multimedia in that it is composed of texts, sounds, and graphical notations. Young is a member of Tomato Grey, an artist collective based in Hong Kong and New York City. The group dances between identities of East and West, Asian and American, and aural/visual, crossing borders and rejecting binaries in favor of unearthing an increasingly complex globalized world. As artists become more and more global, binaries like diaspora/homeland become less divided and more complicated and difficult to define.

Laura Kina, a mixed-race artist based in Chicago, painted Okinawa — All American Food during a trip to Okinawa, a tiny island off the coast of Japan where her father’s family is based. Kina is acutely interested in matters of movement, migration, race, and identity. In this particular image, a local billboard in Okinawa juxtaposes an all-American image and icons of American commercialism with Japanese words. Like Kina herself, the ad is a mixture of multiple identities, histories, and agendas.

At the End of Class...

Biennials/Triennials and Art Fairs

This lecture allows for great potential in analyzing the state of the art world today. Students probably already have some idea of current trends in the art world, from rising auction prices to the Armory Show, from Bravo’s reality TV show Work of Art to Lady Gaga and her Marina Abramovic-inspired art pop. Recent years have also seen an uptick in the influence of celebrities like Jay-Z and James Franco in the contemporary art world. Utilizing pop culture as entry points, you can easily glide into conversations about global biennials/triennials and art fairs that have come to dominate the art world. The art world is a mirror and an agent of melting geographic borders and the boundaries between celebrity and art. This lecture is ripe with works that could serve as prompts for discussion.

Museum Paper

How do local museums address matters of globalization? Do they ignore them or focus on them? If they address such issues, do they do it sufficiently, or do they gloss over some matters? Visit a local museum and explore the galleries with these questions in mind. Consider the structure of the museum and how the art is laid out. If the museum is a very local museum (i.e., not an encyclopedic museum), consider how the museum balances issues of the local versus the global. Assign a response paper based on your students’ findings.

Artist Response Paper

Consider the concepts of globalization and aesthetics. Pick one artist and discuss how the artist’s work addresses concepts of globalization and/or functions as an agent of change. Consider the artist’s role in biennials, his or her gallery representation, or the subject and content of the work itself.