Chinese Art After 1279

First Things First...

Many of us drop into a lecture on China after spending quite a bit of time looking at art and architecture in the west. The survey texts tend to place China after a quick foray into India. This can appear disjointed to students. To tie this content to things you may have already covered, in this lecture it can be helpful to create links between the struggles and innovations Chinese artists faced with those from Italy and other parts of Europe. Who could be an artist? What was the status of an artist? How does patronage work? In this lecture you can ask the students to think about how systems of belief (Confucianism, Daosim, Buddhism) are manifested in art and architecture in China, particularly through landscape painting, but also in the creation of traditional “Chinese” porcelain. For example, you could discuss scholarly literati painting, a tradition that counters the professional practice of court painting.

Comparing earlier Chinese art to that of the present can also be helpful. For example comparing the concerns of the literati painters with those of contemporary artist Ai Weiwei and others. Neil MacGregor’s discussion of intercultural exchange with regards to the “David” Vases ties in well to the issues of East-meets-West and tradition-meets-today. This works quite well with a discussion of Ai Weiwei’s Sunflowers from 2010.

By stressing two themes in this lecture, transmission and politics, the link between diverse art periods and large geographic and chronological shifts can be established. The theme can also be used to address preconceptions of what “Chinese” art is.

Background Readings

Content Suggestions

Teaching the second half of the survey is challenging. It’s hard to cover all of the material from roughly 1200 CE to the present in one class. We often leave the contemporary materials to the end of the semester or quarter, since this is traditionally how the art history texts have presented the material—in a fixed chronological order. But by this time, many of the students have forgotten some of the issues discussed in earlier lectures (and who can blame them?).

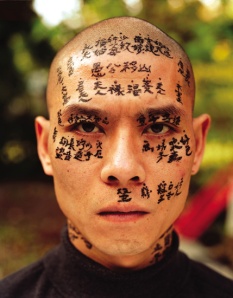

By incorporating at least one contemporary artist into the lecture on China, the students can more easily get a sense of the continuity of the issues that face each generation. This practice can, of course, be applied to other art historical and geographical periods as well. Contemporary artist Ai Weiwei is included in the outline here. Further examples—Zhang Huan and Huang Yan—are contemporary Chinese artists who can be incorporated into the lecture when discussing issues of Confucianism (control, familial authority, and social order) or calligraphy and traditional landscape painting.

In an hour and fifteen minutes, this content area can be investigated through many objects, including:

- Zhao Mengfu, Groom and Horse, 1296, Yuan dynasty (1271–1368)

- Zhao Mengfu, Twin Pines, Level Distance, c. 1300, Yuan dynasty

- Zhao Mengfu, Autumn Colors on the Qiao and Hua Mountains, 1296, Yuan Dynasty

- Fan Kuan, Travelers Among Mountains and Streams, 11th century, Northern Song Dynasty

- Ni Zhan, The Rongxi Studio, 1372, Yuan Dynasty

- Dong Qichang, The Qingbian Mountains in the Manner of Tung Yuan, 1617

- Yin Hong, Hundreds of Birds Admiring the Peacocks, late fifteenth/early sixteenth century, Ming Dynasty

- Shen Zhou, Poet on a Mountaintop, c. 1500, Ming Dynasty

- Shitao, Landscape, c. 1700

- “David” Vases, c. 1351

- Ai Weiwei, Sunflower Seeds/Turbine Hall, Tate Modern, 2010

Glossary:

Album/Album Leaf: An album leaf is a single painting from an album, which is a book where sets of paintings of identical size have been mounted (like a photo album). The paintings are usually related, like scenes from one period of travel or different views of a famous site.

Handscroll: A handscroll was usually about 12 inches high and anywhere from a few feet to dozens of feet long. It could have scenes mounted on it like in an album book or painted directly inside. The scroll could be set on a table and rolled out piece by piece, so the front would be set on the beginning of the roll, on the right, and the scroll would be read from this page to the left, rather than from left to right. The scroll was meant to be read gradually, rather than spread out and displayed all at once.

Hanging scroll: displayed vertically rather than horizontally and all at once rather than viewed piece by piece. The bottom roller of the scroll was usually weighted in order to help it hang.

Large Paintings: Either on the wall or on silk, these works typically decorated palaces, temples, and tombs.

Historical outline: see Lecture Notes.

Creating reading prompts or using Dr. Guintini’s video above can help facilitate a more informed and livelier discussion of of Never Sorry, the Ai Weiwei documentary. Showing the Ai Weiwei version of PSY’s “Gangnam Style”, discussing the subsequent censorship by the Chinese government, and viewing the support videos by Anish Kapoor and the many museums who also responded can be a fun way to re-introduce art and political action into class. Another great resource is Ai’s Twitter account, which is part of his “artistic toolbox” and a platform for him to call people to action and draw attention to his own.

Connect Ai’s practice to earlier discussion of the literati artists who were also participating in politically-minded art making.

Zhang Huan

Information can be found here and here.

Family Tree, 2000.

Huang Yan

Huang Yan’s work makes reference to a Chinese cultural heritage that is innate to every Chinese artist, and one could argue, every Chinese person.

Information can be found here. The porcelain bust can also be addressed within the context of the “David” Vases and Ai’s Sunflower Seeds.

Chinese Landscapes, begun in 1999.

The Cultural Revolution and the Iconic Image of Chairman Mao

A large number of artists also make art that directly addresses that iconic image of Chairman Mao and the effects of the Cultural Revolution and its current evolution. For information on propaganda posters used during the Cultural Revolution see this site.

Zhang Hongtu’, Chairman Mao, #3, 1989.

Li Shan, Rouge series, 1989–93.

Sui Jianguo, Legacy Model, c. 1997.

The three artists above are among several contemporary Chinese artists who index Chairman Mao in their work. Information on these artists (as well as on Zhang and Huang) can be found in the following:

Melissa Chiu, Asian Art Now, 2010; Melissa Chiu and Benjamin Genocchio, Contemporary Art in Asia: A Critical Reader, 2011; Jiehong Jiang, Burden Or Legacy: From the Chinese Cultural Revolution to Contemporary Art, 2007; and Richard Vine, New China Art, 2011.

Andy Warhol’s Chairman Mao (c. 1973) is also an excellent example to either insert into this lecture or for use in the Pop lecture as a reference to past material for the students—making connections between what appear to be disparate cultures.

The print can be discussed in several ways:

- as commodity (in reference to the discussion of the “David” Vases) in terms of Warhol’s own production practices.

- in terms of auctions and the contemporary art market.

- A discussion of Warhol can also fit well into issues of criticisms of the contemporary Chinese government as also raised in the work of Ai Weiwei. For example, in 2013 a new museum of contemporary art in Shanghai, The Power Station of Art, opened an exhibition of Warhol’s work but declined to hang any of his Chairman Mao prints.

- as an example of mass production, which is also as issue for Ai Weiwei.

- with regard to censorship and the Chinese government.

- as a symbol of remembrance, which can link the subject to almost any other art historical period of the semester.

At the End of Class...

Further Resources

Smarthistory on Imperial China