Comics: Underground and Alternative Comics in the United States

First Things First...

This lesson plan covers underground and alternative comics in the United States from the 1960s to the present. Underground and alternative comics are the closest of any American comics to high culture and the avant-garde and could usefully be compared to art house, New Wave, or independent film as occupying a midway point between the avant-garde and mass culture. “Underground comix” were an integral part of the youth counterculture of the late 1960s and early 1970s and were succeeded in the 1980s and 1990s by “alternative comics” that were loosely connected to the indie/alternative subculture of that era. Despite their closeness to high culture, underground and alternative comics have not been considered worthy of incorporation into the field of art history, a prime example of the privileging of high culture over mass or popular culture. This is a hierarchy that has been interrogated and debunked for the past three decades but that nevertheless still remains in effect, albeit in attenuated form. Despite this continuing lack of recognition, underground and alternative comics have aesthetic values of their own that are worth exploring, are significant parts of contemporary visual culture, and can be used to illuminate aspects of society and culture not generally accessible to high art.

Instructors should modify this lesson plan to suit their needs. You can choose to use just a few slides or to mix and match material from this lesson plan with examples from newspaper comics and mainstream comics. There is no standard way of teaching comics in an art history curriculum (or really any curriculum at this point), so go ahead and experiment.

Background Readings

Content Suggestions

Key themes and aesthetic concerns in the early history of newspaper comics can be explored in an hour and fifteen minutes through a variety of examples, including:

- Gilbert Shelton, cover of The Fabulous Furry Freak Brothers #1, 1971

- Kim Deitch, cover of The East Village Other, October 11, 1968

- Clay Wilson, “The Flyin’ Fuckin’ A Heads Stop For Lunch During Their Cross-Country Run,” S. Clay Wilson 20 Drawings, 1967

- Victor Moscoso, concert poster for the Avalon Ballroom, San Francisco, 1967

- Victor Moscoso, “Luna Toon,” Zap Comix #2, 1968

- Poster for Man Ray exhibition at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, 1966

- Yayoi Kusama, Anti-War Naked Happening and Flag Burning, 1968

- Robert Crumb, “Whiteman,” Zap #1, February 1968

- Robert Crumb, “Cubist Be Bop Comics,” XYZ Comics, June 1972

- Robert Crumb, cover of Gothic Blimp Works Ltd. #2, comics insert in the East Village Other, 1969

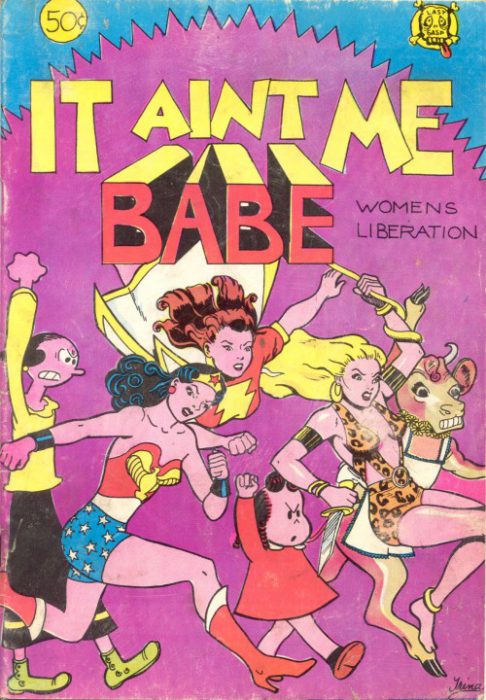

- Trina Robbins, cover of It Ain’t Me Babe, July 1970

- Willie Mendes, “Oma,” in It Ain’t Me Babe, July 1970

- Robert Crumb, “A Word to You Feminist Women,” Big Ass Comics #2, 1971

- Aline Kominsky-Crumb, cover of Twisted Sisters Comics, 1976

- Harvey Pekar (script) and Val Mayerik (art), American Splendor #10, 1985

- Harvey Pekar (script) and Robert Crumb (art), “The Young Crumb Story,” American Splendor #4, 1979

- Dan Clowes, cover of Eightball #11, June 1993

- Dan Clowes, Act Three, “Crime and Judy,” in David Boring, 2000, originally published in Eightball #21, February 2000

- Gary Panter, cover of Raw vol. 2, #1, 1989

- Art Spiegelman, Chapter 2, “Auschwitz (Time Flies),” in Maus II: And Here My Troubles Began, first published in Raw vol. 2, #1, July 1989

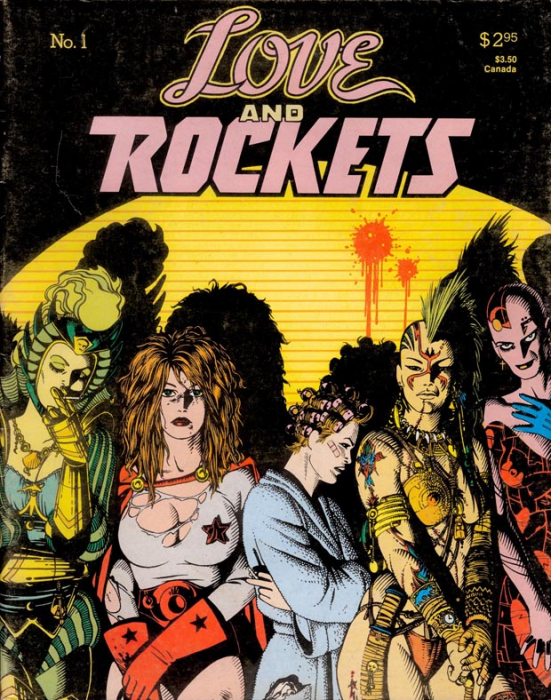

- Jaime Hernandez, cover of Love and Rockets #1, 1982

- Jaime Hernandez, “Ninety-Three Million Miles from the Sun…and Counting,” Love and Rockets #30, July 1989

- Alison Bechdel, two-page spread from Fun Home, 2006

Glossary:

Comic book: A comic book is a self-contained pamphlet containing comics and is distinguished from the much shorter comic strip, which is usually limited to at most one full page, and the much longer graphic novel, which is typically at least 100 pages. American comic books are staple-bound and pamphlet-sized, with 24–32 pages being standard, but they may be as short as a few pages or as long as 64 pages.

Comics: The exact definition of what makes something a comic has been a matter of some dispute among comics scholars. A rough definition is that comics use a combination of words and images in sequential panels to tell a story. Comics are differentiated from illustrations, in which the narrative is conveyed primarily through the text and the text and images are visually separated; comics interweave text and images and rely equally on both. Comic strips, comic books, and graphic novels are all examples of comics.

Creator-Owned: Creator-owned comics are comics whose copyright belongs to the artist who made them, allowing the artist to profit off of their comics’ success. Creator-owned comics may be self-published or published by a publishing company. Underground and alternative comics are typically creator-owned, whereas mainstream comics are typically work-for-hire.

Graphic novel: A graphic novel is a lengthy, book-sized comic. Most graphic novels are originally published as comic books and then collected into anthologies (sometimes known as trade paperbacks).

Gutter: The gutter is the space between panels. In Understanding Comics, a classic analysis of the comics medium, Scott McCloud argues that the gutter is the most distinctive aspect of the comics medium and is essential to its semiotic and aesthetic operation.

Panel: The panel is the basic unit of organization of the comics page. Panels are typically rectangular, framed by an outline, and arranged in a grid, but other types of panel and panel organization can be used to alter the pace, mood, or aesthetics of the page. Panels can have irregular or unusual shapes, can lack borders on some or all sizes, can have colored or textured outlines, and more free-form structures can be substituted for the grid.

Self-Published: Self-published comics are published by the artist who creates them rather than by a publishing company. Self-publishing has been used by some underground or alternative cartoonists but not by mainstream cartoonists.

At the End of Class...

The end of class is a good time to ask students to reflect on the relation between comics and high art and on their own experiences with comics. You could pose the following questions:

- Do they relate to comics more easily than to high art?

- How are the cultural spaces of comics and high art different from each other?

- Do cultural hierarchies continue to privilege high art over comics?