Engaging the Masses: Activities for kicking off a jumbo class

Guest Author: Mya Dosch

Students in jumbo classes often hope that they will be able to slink into the lecture hall, let the lights dim, and passively receive information from the lecturer—or remain incognito as they finish their calculus homework. If you are hoping to do anything but lecture—from a throwing in a few discussion questions to a full flip of the classroom—this inertia is deadly. The first few minutes of a class matter: they set the tone for students’ engagement for the rest of the session. If I start a class by lecturing for 5-10 minutes without open questions or student activities, I can sense the energy draining from the room, and often have a hard time shifting into other learning modes later in the period.

I teach a survey art history course that is required of all undergraduate students, so I often have to overcome students’ skepticism about “yet another intro-level course.” What follows are a few types of activities that I use as “hooks” to foster student engagement at the beginning of class. They also help students to connect to cultural artifacts that may seem arcane, irrelevant, or just plain boring to them at first glance. Drawing on John C. Bean’s excellent discussion of “exploratory writing,” I try to keep these discussions and writing exercises “low-stakes.” In other words, I ask questions to which there are no right or wrong answers, and grade in-class writings only for adequate completion, and not for grammar or spelling. Many of these writing activities also serve as my alternative to the tedious process of calling roll or the unreliable sign-in sheet. I grade these writings quickly, giving students full credit (10 points) if their response shows reflection and effort, and partial credit (5 points) if a student was present but did not adequately complete the assignment. The points that students receive for these writings count toward their attendance/participation grade.

Here are a few ways I try to keep students engaged…..

Brainstorming as a preview of class content:

-I ask students to shout out all of the attributes and physical characteristics that they associate with the Buddha (“What does the Buddha look like?”) and we compile a list on the board (“Big belly,” “eyes closed”) to launch our discussion of Buddhist sculpture in Mathura. We can then refer back to the board throughout the class to compare our list to Mathuran depictions. What matches up from their brainstormed list? What is different, and why?

-Discussing Ancient Egyptian funerary statues, I ask students to brainstorm 1) what images come to mind when you think of ancient Egypt? and 2) Where did these images come from? Our somewhat-irreverent discussion of the vision of ancient Egypt put forth in Indiana Jones and The Mummy Returns leads to a discussion of Egyptian revivals and then Ancient Egyptian art.

Brainstorming activities also provide a chance to gage the knowledge and interests already in the room, and to shift the rest of the class period accordingly.

Brainstorming as a review from the previous class:

-As a review of both our discussion of cubism and our class on Caribbean modernisms, I ask students to brainstorm possible reasons that Pablo Picasso’s Demoiselles is included in every major Intro to Art History textbook, but Cuban painter Wifredo Lam’s The Jungle is rarely added. Lam’s painting is also part of the MoMA collection and is just as canonical in histories of Latin American art. On first glance, students often suggest that Lam was “copying” Picasso’s cubism, or that his 1943 painting came “too late,” echoing the European modernist fetishization of “originality.” We then go on to problematize these distinctions (What sources did Picasso himself draw upon? How might Lam’s painting help us to re-think Picasso’s interest in African art?), modeling critical reading and showing that even a textbook has biases. Students have also brought up current Cuban/U.S. relations, allowing us to discuss how contemporary politics affect our interpretations of history.

-To explore the foundational concepts of Impressionism at the beginning of the following class period, I tell students that “Where are the Impressionists?” is one of the most frequently asked questions at the information desk of the Met. I then have students brainstorm possible reasons that Impressionism is so beloved to this day. Their answers range from “It’s totally different to see Impressionism up-close in a museum” (cue a review of impasto) to “we prefer to look at images of leisure” (cue a review of Nochlin’s essay “Morisot’s The Wet Nurse: The Construction of Work and Leisure in Impressionist Painting.”)

Other activities that require thinking “outside the time period:”

–To introduce the group portraiture of Hals and Rembrandt, I show the class a generic elementary-school class portrait and ask them to write a short description of the image to get at the conventions of group portraiture. I then ask a few students to share their writings, and we go on to compare these conventions to both early Dutch group portraiture and portraits by Hals and Rembrandt.

Sketching:

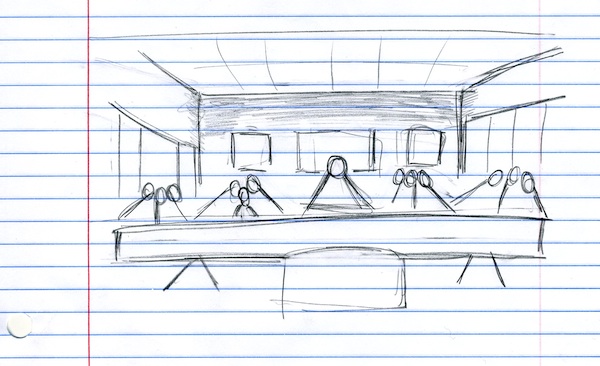

–I begin my class on Leonardo’s Last Supper by having students each sketch the major lines and shapes that make up the fresco. I ask them to ignore the details, encouraging them to squint at the image to isolate the major forms. Drawing inevitably provokes anxiety in some students, so I assure them that they will not be graded based upon on the quality of their rendering, but instead on their completion of the project. Then, I ask students to share things that they noticed about the structure of the painting as they drew. This serves as an introduction to our discussion of Renaissance notions of perspective and balance. Trying to get students to describe Leonardo’s compositional choices without such an activity would only engage a few students; a sketch helps more students to focus on the artwork’s structure and participate in the conversation.

Jesse Day has an entire post on the value of drawing in the art history classroom.

Creative writing

-After telling the story of the Burghers of Calais, but before showing Rodin’s sculpture, I ask students to split into small groups. These groups have 15-20 minutes to come up with a proposal for a statue that honors the Burghers. I ask students to write a description of the salient visual features of their proposed sculpture: the poses, the medium, the composition, the scale, etc, and then to briefly justify each of these decisions. This allows them to practice both descriptive writing and visual analysis. Each group also draws a rough sketch of their design. We then come together as a class and act as the town council of Calais. Several groups “pitch” their sculptures and field questions from their classmates. This gives students a greater understanding of both 19th-century conventions for memorial sculpture and the ways in which Rodin’s approach transgressed these conventions.

–After completing two readings on Medieval pilgrimage churches, one secondary source (A few pages from Ashley and Deegan’s excellent Being a Pilgrim: Art and Ritual on the Medieval Routes to Santiago) and one short excerpt from Abbot Suger, I ask students to write a first-person narrative that completes the following sentence: “I entered the church, and approached the relic…” This allows the students to engage with major themes from the reading as they describe, for example, how they talked to the relic as if it were a living saint and prayed that it would produce a miracle for their family. Such creative writing not only engages students who may not have much experience—or interest—in formal academic writing, but also makes for much more interesting grading than a traditional “summarize the main points” prompt. I incorporate some creative-writing prompts into my essay exams for these same reasons.

These are just a few possibilities. Jessica Santone presented a paper at CAA 2013 entitled “Acting out: Reenactment in the Art History Classroom,” which discussed having small groups of students create “living dioramas” of paintings in order to better grasp their figural and compositional strategies. I would love to crowd-source a much longer list in the comments section below.

Mya Dosch teaches Modern Art and Introduction to Art History as a Graduate Teaching Fellow at Brooklyn College, and is currently completing her PhD in Latin American art at the CUNY Graduate Center. Before teaching in the classroom, she worked in museum education, getting 7-year-olds excited about The Cloisters and 70-years-olds excited about Sol LeWitt.

Ashley, Kathleen and Marilyn Deegan. Being a Pilgrim: Art and Ritual on the Medieval Routes to Santiago. Farnham, Surrey: Lund Humphries, 2009. (I assign pages 108-109.)

Bean, John C. Engaging Ideas: The Professor’s Guide to Integrating Writing, Critical Thinking, and Active Learning in the Classroom. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass, 2001. (Particularly chapter 6 on “Informal, Exploratory Writing Activities.”)

Nochlin, Linda. “Morisot’s Wet Nurse: The Construction of Work and Leisure in Impressionist Painting.” In Perspectives on Morisot, edited by T.J. Edelstein, 96-97. New York: Hudson Hills Press, 1990.

Suger. “The Other Little Book of the Consecration of the Church at St.-Denis.” In A Documentary History of Art, Vol. 1, edited by Elizabeth Holt, 36-39. New York: Doubleday, 1957

Note: several of these techniques grew from discussions with colleagues during an Art History Pedagogy course at the CUNY Graduate Center in Spring 2011. Thanks to Liz Donato and Michelle Fisher for their suggestions on sections of this post.

Thanks so much for this fantastic discussion! I will definitely be using some of those icebreakers in future classes….

To contribute, I do thematic lessons based on the idea of sacred spaces and objects– so as an icebreaker I had students split up into groups and discuss what makes an object or a space “sacred”. I had great success with students who don’t normally participate in class, because everyone was able to consider what they consider sacred in their own lives.