Re-Designing the Survey Course, Textbook-Free

[Ed. Note–we’re proud that AHTR started exploring ways to re-think textbooks as part of the art history survey as far back as our first month online. The post below revisits this conversation 18 months later, and invites further conversation.]

After teaching the global art history survey courses for more than a decade, the prospect of converting the class into a textbook-free one was daunting. By this point, my class runs like a well-oiled machine. Even when publishers update editions of my textbook or switch to a different author, I have learned to roll with those changes with relative ease.

But this academic year, the price of my department’s standard global survey textbook reached $167.71. If you multiply $167.71 by 150 students (the enrollment capacity for one section of the class–and we run at least two each term), the textbook cost had reached a staggering $25,156.50 per class–the equivalent of in-state tuition for one student for 3½ years at my institution. While cost is a secondary concern to learning outcomes, as a professor at a large public university in the state with the lowest median household income in the nation (Mississippi), I just couldn’t justify requiring that purchase. (And that’s assuming that students weren’t opting out of buying a textbook in the first place. Let’s be honest–many don’t even bother getting the more expensive required textbooks.)

So when my academic division offered a modest summer stipend to help offset the cost of converting courses with large student enrollments to free online resources in lieu of paper textbooks, I applied and received a grant for the development of a textbook-free art history survey (covering the Renaissance to today) to launch in the fall of 2014. Upon accepting the stipend, I committed to run the textbook-free course at least twice, and to provide regular progress reports/reflections on the project with my supervisors.

I am committed to finding quality free resources that rival–and even improve upon–the information available in the survey textbooks. At first, this concerned me, even though I have contributed short essays to Smarthistory and regularly integrate various online resources into my survey teaching. Would I be able to curate a coherent, compelling textbook-substitute experience?

So I panicked, and did what most people do when they are stressed: I logged into Facebook. This was a fortunate decision in the disguise of procrastination. While I was avoiding thinking through my response to this challenge, I made a quick post to the AHTR Facebook page to see if anyone else out there had any experience with such a project, or if I would be starting from scratch.

As it turns out, I am behind the curve at going textbook-free. Several people replied to my post on AHTR, and many even generously offered to share their materials with me. Particular thanks go out to Karen Shelby, Michelle Millar Fisher, and David Boffa for giving me syllabi and pointers from their own experiences with the textbook-free survey transition. I was thrilled to hear that almost everyone who goes textbook-free never goes back to them! I also found these sample virtual-textbook syllabi from Smarthistory/Khan Academy quite useful for their integrated links to learning objectives, estimated time for viewing/reading assignments–which I anticipate students will appreciate, and vocabulary.

I opted to base my syllabus [download here] on the layout of the Smarthistory/Khan Academy syllabus (Renaissance to Modern), and supplemented with my own Modern and non-Western material. (Smarthistory now has a Modern syllabus available, I should mention.) But my biggest challenge was finding non-Western links that cover my specific time periods at the desired depth/breadth. Smarthistory is currently developing the non-Western content on its website, so I turned to museum sites, online exhibition archives, reviews of those exhibitions, virtual tours of monuments, the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s collection and timelines, and English-translated videos hosted by various cultural societies.

As I worked on my syllabus, I marveled at how many of these resources offer a greater depth of coverage per image than a textbook can. I became excited about the prospect that the virtual textbook of links that I have curated might even be better than the even depth offered by the conventional paper book.

Still, I encountered and foresaw a couple obstacles and lingering questions on my summer path to abandoning the textbook:

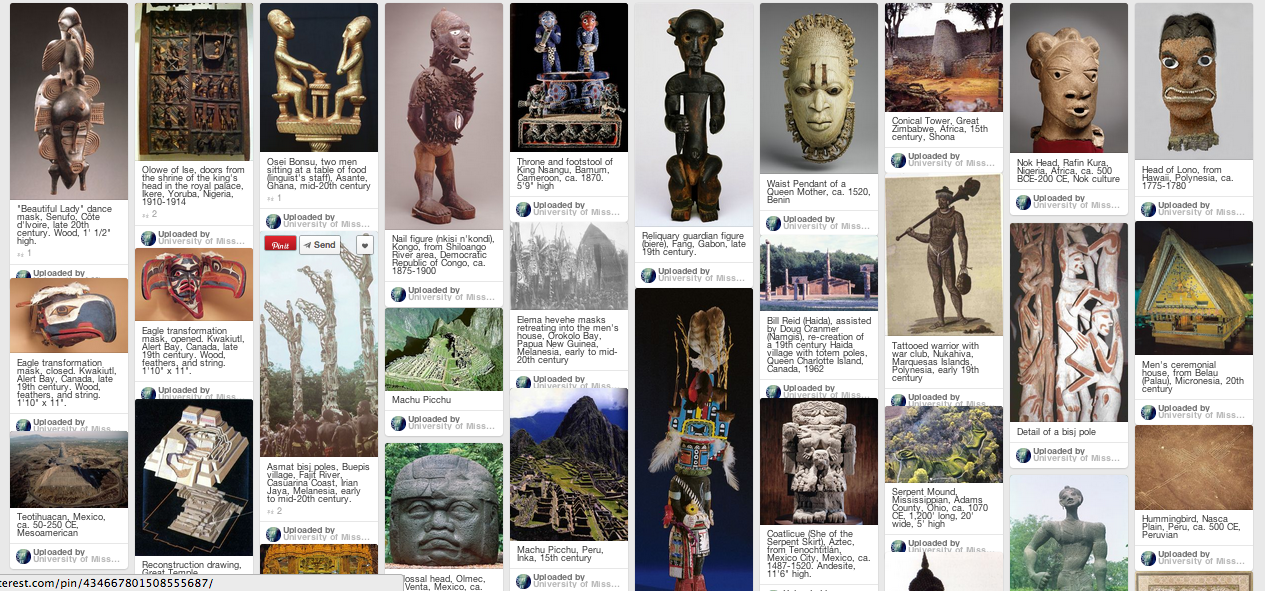

– Where would my hyperlinked syllabus document “live”–so that its links could be accessible to students, but would not get deleted or lose hyperlinks when BlackBoard course sites are archived at the close of every term? Should I start my own site, since my institution does not support faculty websites? In a practical sense, how do I launch and build a web site? To help solve these problems, I hired a technology-savvy graduating MFA student for 50 hours over the summer to help launch a web site to host these materials. (Since the website is funded by me, it also eventually will function as my professional online presence, when I find time to develop that part of the site.) At the suggestion of my assistant, we decided to use WordPress for the site, and to supplement it with a separate Pinterest page for hosting key images. (That Pinterest page also functions as the study page for my the annual assessment exam my department gives to graduating seniors to measure learning outcomes for NASAD accreditation. But that is a subject worthy of a completely different post.)

– Will the constant updating and tending of these hyperlinks be time-intensive? Yes, I anticipate it will be. But would it be any more or less involved than the usual retooling we would do for updated paper-based textbook editions? We shall see.

– By nudging students to patronize online resources, am I subverting a publishing industry (of my peers) that needs support? I am still torn about this ethical issue, and have no answers.

But enough about me. What obstacles might my students face?

– Access. Not all of my students own laptops, iPads, smartphones, or other electronic devices. Many of them will need to make trips to the computer labs to view assignments. Will they?

– My students inevitably will need some troubleshooting help with the WordPress and Pinterest sites. This will present a learning curve for me, too.

– ‘Highlighters’ Make New Habits? Some students prefer highlighting a piece of paper over passively watching videos or reading from a screen, or highlighting by touching a screen. Could the digital technology make converts of my paper-loving devotees?

– Driving Them Right Into the Land of Distraction. I have yet to encounter a disciplined group of students that can use laptops/iPads in class without occasionally veering to checking e-mail or social media–or worse. (One of my colleagues busted a student who almost watched an entire soccer game during a lecture on Classical art!) Would I just be inviting them to be yet more distracted? Our “traditional” student body always has known the internet as a component of everyday life. Consequently, managing the results of the sensory conditioning that transpired from multifaceted, hyper-stimulating media is a central challenge for them. Accessing class materials online will force the confrontation of these attention-span issues.

In sum, as I finish the tasks of uploading and refining my syllabi and links to the web site this month, I anticipate that the work will not be done. Rather, I expect it will just be the beginning of my process of incessant course redesign, as students test this new method of accessing information and ferret out its glitches. I will keep you all posted, and invite you to drop by www.beldenadams.com as the project develops and changes.