Seeing Music

While I was working at the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum in Boston, I attended a session about Visual Thinking Strategies. The method’s ingenuity lies in its simplicity; participants study an image and their observations are teased out with subtle and careful questions, revealing a startling level of nuance. It struck me as a wonderfully refreshing way to engage students in a conversation about the unfamiliar, and I started to wonder if some of these principles could be applied to the study of music.

For the past three years, I have taught undergraduate Music History and Music Appreciation courses at Baruch College (CUNY). (I am a musicologist by training, and am currently writing a book about musical culture in the rubble of postwar Berlin.) For students who do not read music, the discipline can be intimidating at the very least, hermetic at the very worst. Conventional wisdom has it that Music History students need to be told what the important points are in the score. Only by dogmatically pointing out critical moments in the piece (“Ah, yes, here we are at the second theme….Now the development…Finally, a return to the recapitulation!”) can the listener fully grasp the piece’s form and the composer’s intentions. I began to wonder if there could be a kind of middle ground, one that bridged the gap between guided listening and allowing the student to create his or her own sonic map of the piece. For students who do not read music, how can the visual act as a bridge between the musical score and the sonic product? In other words, how can we integrate the visual into a medium that occurs in time and space?

I’d like to focus for a moment on Arnold Schoenberg (1974-1951), a Modernist giant whose music signaled a jarring break with tonality. Musically, Schoenberg went through a number of different stylistic periods, experimenting first with a late Romantic idiom, Expressionism, Twelve-Tone Music, and finally, a combination of these styles. Bracing and uncompromising, Schoenberg’s music has polarized musicians, critics, and audiences alike for his rejection of the tonal system.

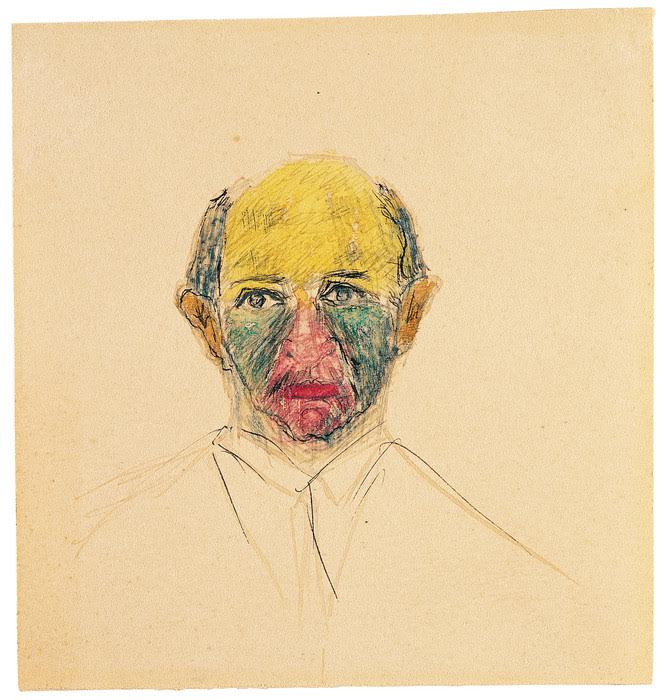

Aside from his work as a composer, Schoenberg was also an amateur artist who produced dozens of sketches and paintings in his lifetime. Schoenberg’s visual art sometimes speaks to his compositional transitions; he created Self-Portrait (1921-1925) around the same time that he began writing twelve-tone music. (Twelve-tone music features a tone row in various mathematical permutations, and one can hear it either as highly ordered chaos or as a new musical path forward. Or perhaps we can hear it as both?)

The image is particularly evocative because of the bold color choices Schoenberg makes for the various regions of his face; students have had all kinds of different theories about why he made the selections he did. (Schoenberg was reticent on this point.)

The more I teach, the more I realize that asking students to describe what they see (rather than what they hear!) can serve an empowering function. The visual provides a provocative point of entry for students who would otherwise feel uncomfortable talking about musical elements right off the bat, and an image can inform an auditive experience or work against it.

As the Nazis rose to power in 1933, Schoenberg left his position at the Prussian Academy of the Arts in Berlin, eventually relocating to Los Angeles where he taught at UCLA. Like many of my students who have come to New York to flee persecution, Schoenberg, too, had to reinvent himself in an unfamiliar place.

A common refrain I hear from listeners is that they find Schoenberg’s work “difficult” or “unapproachable.” Perhaps that’s because it is. In order to make his compositions more accessible, I began using images not only painted or drawn by Schoenberg, but also photographs from his daily life in California. (Aside from his predilection for table tennis, Schoenberg was also known to play tennis with George Gershwin on occasion.)

Linking musical and visual cultures can only enrich and inform the classroom experience. A time and place that might sound remote from our own can be approached through the lens of a camera, and a single snapshot can collapse the past 80 years. In the photograph above, we see Schoenberg focused on only the game, his eye on the ball.

Perhaps only by seeing music can we really hear it in the first place.