“I read it, but I don’t get it.”

How many times have we heard students utter such comments? Recently, a student who had excelled in my Survey II class came to my office hours. She was visibly shaken and described her struggle in her upper level art history course. She told me she would read the article, understand every single word, take notes and come to class without understanding the class discussion. She wondered if she had even read the same article. Thinking back, I remember feeling exactly the same. So what’s going on here? Students don’t have adequate background information to contextualize, learn and remember difficult readings. To help them develop critical reading skills I introduce a two-step process: analysis and evaluation. To analyze the text, they learn the process of argument diagramming. To evaluate the text, they assess its rhetorical elements. Combined, these skills provide students with a firm foundation for critical reading.

To begin, I introduce the process of argument diagramming. Most people are familiar with some sort of diagram, they come in many forms and are called by many names: concept maps, mind maps, infographs, and so on. An argument diagram is a visual map of the key components and how they relate to each other. This helps students build schema.

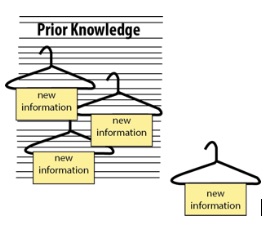

Schema is prior knowledge on which we hang new information. We need to categorize new information according to something we already know so we can learn it and remember it. If we have little prior knowledge (schema) then we can easily become overloaded with new information. This is where argument diagramming can help. They force the reader to identify the functions and relationships of the various parts of the text, building schema along the way. When done right, argument diagrams provide instantly legible pictures that are easy to compare, share and grade; making them an ideal reading activity for difficult texts.

Argument diagramming has an internal logic and vocabulary.[i] To ensure that we’re all working with the same conventions and the same language, I introduce a handout with reading instructions, rules, and indicator words. Beginning with a short and easy text, I provide a partially completed diagram with only the conclusion filled in. The students read the text in class, then as a group they identify the premises using the conventions explained in the handout to complete the diagram.

Groups will then project the diagram to edit and comment on their colleagues’ work.[ii] The ensuing class discussion will focus on the structure of the text; and they are lively discussions because students have solid and meaningful comments and questions to share. Collectively, we tweak and refine our diagram yielding a common image of the text’s structure that we will use as a future study guide. At this point, I explain to the students that diagramming the text facilitates our comprehension of the content, but now we need to evaluate the text because critical reading involves both analyzing and evaluating.

Returning to the text, I guide the students through a rhetorical evaluation by considering audience, ethos, pathos, and logos. They are often familiar with this process, recognizing it from a high school or college English class. I build on the opportunity to consider these rhetorical elements and how they’re used in our reading. A simple chart of these elements helps guide our discussion or, if time is short, can serve as a follow up assignment. Either way, the result of this introductory lesson gives students the skills to analyze, diagram and evaluate—all essential critical reading skills.

The reading assignments that follow build on their skills. I assign a reading for homework, reminding students of the instructions on the handout: skim and annotate, read and annotate, identify and write statements, prioritize, diagram, evaluate. Do they do all of this for homework? Not always. I follow up with a think/pair/share activity using the diagram and evaluation chart. The result is a class that is engaged with the text, learning the content, evaluating the argument and applying it to their course materials. Diagrams and rhetorical charts serve as the basis for our discussions and assessments throughout the remainder of the term, to reinforce their critical reading skills. And remember, that is the real objective.

A few words of caution: it is easy to get caught up in the details of diagramming and lose sight of the big picture. Don’t do it. I have to remind myself that the objective of the activity, and of the course, is for students to be able to read critically a scholarly art history text. By working the structure of the argument and evaluating the rhetorical elements, students are doing just that. Take a back seat as they work it and remember that the process is more important than the product. My hope is that they will continue to use this process and to refine their skills as they continue their academic career.

Another caveat: avoid getting trapped in the technology. There are hundreds of Apps that allow students to diagram digitally and offer varying levels of functionality.[iii] I have found that the diagram software, Popplet Lite, worked best for us. It’s designed for preschoolers—it’s simple and intuitive. The faster students begin working the text, collaborating, and projecting their diagrams to the class, the better. They can also upload their diagrams to the course L.M.S. for assessment. The Apple TV or an Android screen-sharing device can project from the student’s phone, tablet or laptop to the classroom screen. This allows me to yield the floor of the classroom to the students. It is their class; they create the content and drive the discussion.

The response has generally been positive, though I know I make them work harder on the texts. Students have shared that it is time consuming and demanding. However, their written responses on essay exams have shown a significant improvement in factual recall, reasoning and transference to new material. In the short term, I’d like to conceive of ways for students to replace the textbook with their diagrams. In the long term, I hope that students will internalize the process for a lifetime of critical reading.

[i] “Argument Diagramming Open and Free,” Carnegie Mellon University, Open Learning Initiative, accessed May 17, 2018,

[ii] All of my students have an iOS device, so I use an Apple TV for them to project from their devices to the screen. There are many diagramming Apps available that serve this process well.

[iii] These are some of the Apps that I have used: VUE, Cmap, Coggle, xMind, Popplet, Prezzi, and Logos. For an extensive list and description of diagramming tools, see http://www.phil.cmu.edu/projects/argument_mapping/