Activating the Classroom: Correcting Museum Labels as an In-Class Writing Activity

[Author: Izabel Galliera. Isabel is an Assistant Professor of Art History in the Department of Art and Design at Susquehanna University in Pennsylvania. In addition to teaching art history, she collaborates in overseeing the interdisciplinary Minor in Museum Studies. Her research interests are at the intersection of art, politics and social justice, contemporary art in a global context with a particular focus on activist art forms and practices, socially engaged art, theories of public space and social capital, histories of exhibitions, and contemporary curatorial models for exhibition making. Her book Socially Engaged Art After Socialism: Art and Civil Society in Central and Eastern Europe was published in 2017.]

This past spring 2020 semester I taught the upper 300-level course Women in Art at Susquehanna University, a liberal arts institution located in Snider County in central Pennsylvania. The course adopts both a chronological and a thematic approach. It considers the presence and representations of and by women in art during ancient times, the Renaissance and Baroque periods. It also considers such themes as “Women, art education and patronage in the 18th Century,” “Sex, class and power in 19th century England,” and “Feminist Art Generations since the 1960s.” the only pre-requisite is that the students must have reached sophomore level to be able to enroll. For the majority of the 25 students in the class, this is their first art history class in college. The class meets twice a week, in the afternoon, for 90-mintes, which can be a long time for both students and instructor.

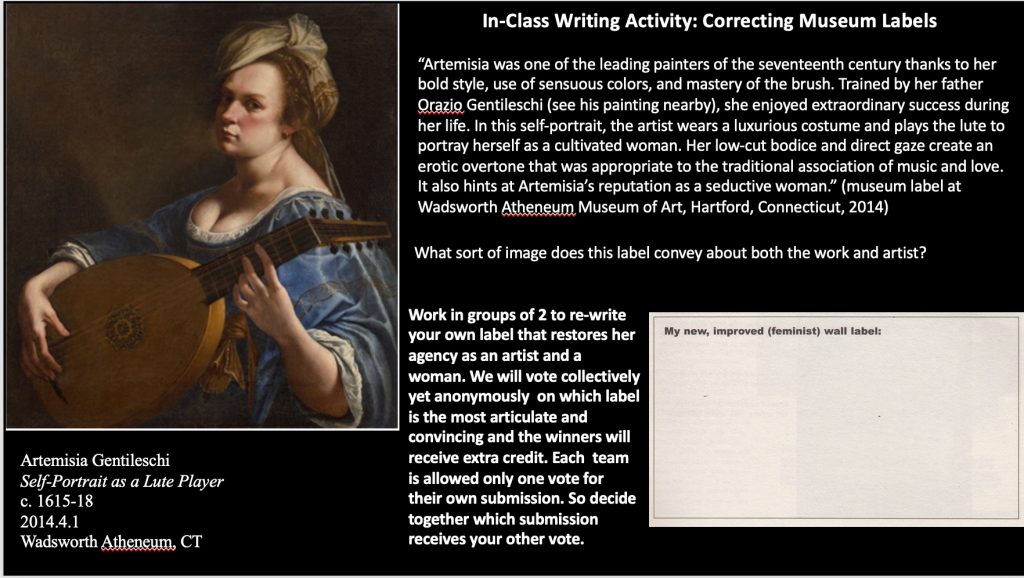

Over the past few years, I have focused on learning and developing pedagogical approaches that rely less on full class lecture and more on creating an environment for active learning through goal-based activities. Each time we meet I always try to design at least one class activity in which students actively engage with the assigned material. For example, on a Tuesday class, we discussed the topic “Baroque Women Painters: Woman as Agent vs Genius.” One of the assigned articles students had to read was Mary Garrard’s “Artemisia’s Hand.”[i] While looking at large projections of a number of self-portraits and portraits by Artemisia Gentileschi and her male contemporaries, we talked about connoisseurship and discussed how the author looked at the way hands are depicted in order to prove the attribution of certain works to the Italian painter Artemisia Gentileschi (1593 – 1653). Garrard insightfully commented: “Like faces, hands have a gender dimension. They are the locus of agency, both literally and symbolically. […] It is through their hands that Artemisia’s women take on the world and confront adversity.”[ii] We observed how gender norms have been inscribed in the way women’s hands have been depicted in various works of art. Strong, assertive and large hands of women can be noted in works by Artemisia Gentileschi. Soft, passive and delicate hands of women appear in works by Orazio Gentileschi and other contemporaries. We also discussed how art does not simply reflect life but contributes to sustaining dominant tropes of gender inequality.

I wanted an in-class activity that not only applies all these ideas to the context of 17th century Italian art but also makes them relevant for the present. I aimed to provide students with a platform to apply what they learned. I wanted them to engage in critical thinking and writing and to practice visual analysis – the lingua franca of art history. How can I accomplish all this by means of a single, fun class-activity?

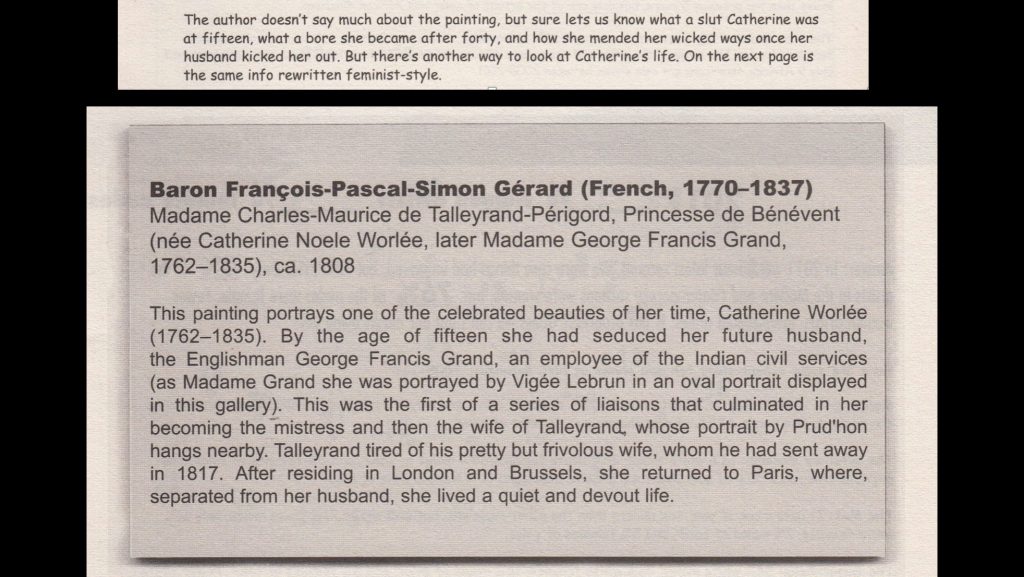

As I was preparing for class and reading Garrard’s reference to Keith Christiansen’s “dismissive and defamatory wall labels at the MET” for the 2002 Orazio and Atermisia Gentileschi exhibition at the Metropolitan Museum of Art (MET), I was instantly reminded by the Guerrilla Girls’ Art Museum Activity Book, unfamiliar to students. particularly their “Activity #5: Correcting Wall Labels.” In their bold, critical and caustic style, Guerilla Girls corrected a label on a work of art by Baron Francois-Pascal-Simon Gerard (French, 1770-1837) displayed at the MET (pictured here). I shared these with my students right before I presented them with the prompt for the activity that they were expected to complete in the last 30minutes of class.

While the Activity Book was unfamiliar to students, they have been acquainted with Guerilla Girls’ unorthodox approach to art history since one of the required readings for the course was The Guerilla Girls’ Bedside Companion to the History of Western Art (1998) by GG. As documented in their weekly reflection papers, students loved their informal, direct and sarcastic style of writing. For most classes (though not for this Tuesday’s class), over the course of the semester, students were assigned a few pages relevant to the topic covered in a particular session.

I knew I wanted to create a similar in-class activity where students are presented with an existing museum label for a work of art by Artemisia Gentileschi, a female artist they read about and discussed in class. They were asked to work in pairs to re-write a museum label that appeared in the 2002 Orazio and Atermisia Gentileschi exhibition at the MET, in a way that it restores her agency as both an artist and a woman. Obviously, for this assignment to work I needed an actual museum label.

I emailed Dr. Garrard and while she did not have copies of “the defamatory wall labels,” she confessed that shockingly sexist wall labels from the 2002 Orazio and Atermisia Gentileschi exhibition at the MET “have been softened in the exhibition catalogue. She explained that “we can gather differences of gender perspectives in the separate commentaries on Cleopatra written by Keith Christiansen (who attributed the work to Orazio Gentileschi) and Judith W. Mann (who attributed the work to Artemisia Gentileschi), cats. 17 and 53, respectively.”[i] The catalogue for the 2002 exhibition is available on line, at no cost, on the MET’s website.[ii] I also reached out to the MET Archives for copies of the exhibition labels, but I received only the wall text, and not labels. I was informed that the MET is currently engaged in a long-term project to digitize all the press kits of past exhibitions that typically include wall labels and text.[iii]

Instead, a 2014 museum label at the Wadsworth Atheneum Museum of Art located in Hartford, Connecticut, became part of my class-activity (see above first image). Maeve Doyle, a member of the online FB Art History Teaching Resources group drew my attention to a rather sexist label on Artemisia Gentileschi’s Self-Portrait as a Lute Player that entered Wadsworth Atheneum’s permanent collection in 2014. It is no coincidence that the Self-Portrait as a Lute Player was displayed in the same gallery with Orazio Gentileschi’s Judith and her Maidservant. The difference in the labels is striking. For example, the label for the work by Artemisia Gentileschi refers to the artist by her first name while the label for the work by Orazio Gentileschi refers to the artist by his last name. The label at the Wadsworth Atheneum worked perfectly since it indicated the ways in which contemporary interpretations of works by Artemisia Gentileschi in museums both sustain and perpetuate a patriarchal gender ideology.

Submissions from students varied. The majority of them displayed an understanding of the problematics of gender-based interpretations for the works of female artists. We began the following class with students pairing up with the partner they worked with in the previous class to pick the best label. Here is the one that received most votes:

Corrected Museum Label:

“Artemisia Gentileschi was one of the leading painters of the seventeenth century thanks to her bold style, sensuous colors, and mastery of the brush. Trained by her father, Orazio, she enjoyed extraordinary success during her life, while cultivating her unique style. In this self-portrait, she portrays herself as a multifaceted, educated, and cultured woman. Her lute shows her discipline in practicing this beautiful instrument, while her fancy clothes are a signified of her social status as a respected and accomplished female artist in a male-dominated culture.” (students in Women in Art course at Susquehanna University, Spring 2020)

Original Museum Label:

“Artemisia was one of the leading painters of the seventeenth century thanks to her bold style, use of sensuous colors, and mastery of the brush. Trained by her father Orazio Gentileschi (see his painting nearby), she enjoyed extraordinary success during her life. In this self-portrait, the artist wears a luxurious costume and plays the lute to portray herself as a cultivate woman. Her low-cut bodice and direct gaze create an erotic overtone that was appropriate to the traditional association of music and love. It also hints to Artemisia’s reputation as a seductive woman.” (Wadsworth Atheneum Museum of Art, Hartford, Connecticut, 2014)

Collectively, we discussed the merits of the winning label. For example, we noted how the artist is referred to by both her first and last names, instead of her first name. Moreover, we observed how sexual references, such as “low-cut bodice,” “erotic overtone” and “seductive woman” were eliminated and replaced with empowering attributes, such as “her unique style,” “respected and accomplished female artist in a male-dominated culture” that clearly restores her agency.

With this in-class activity students gained a platform to apply what they learned. For 30 minutes they become museum curators and educators. They engaged in critical writing and thinking by re-writing a short text in light of what they have learned via assigned readings and in-class discussion. They practiced visual analysis by anchoring their responses around visual clues from the work of art. While working to confer agency to the artist, students also gained agency and were in the driver seat for writing a new museum wall label. My hope is that students will question what they read in museums to a greater extent. Museum labels are powerful, they inform the experiences of viewers. They can both maintain and challenge gender norms in a patriarchal culture. It is important for visitors to be on the lookout for social and cultural biases that may be more or less inadvertently perpetuated.

[i] Mary Garrard, email message to author, February 9, 2020.

[ii] Keith Christiansen and Judith W. Mann, Orazio and Artemisia Gentileschi, MetPublications: 2002, accessed, February 5, 2020 https://www.metmuseum.org/art/metpublications/Orazio_and_Artemisia_Gentileschi?fbclid=IwAR2RUMiWkBV11R1cYKdK3_7VmW5YuOitrvSawYy8otLqNM4VUJTyBYvjgPo

[iii] “The Met Digital Collections,” accessed, February 5, 2020, https://libmma.contentdm.oclc.org/digital/collection/p16028coll12/search/searchterm/wall

[i]Mary Garrard, “Artemisia’s Hand,” in Reclaiming Female Agency. Feminist Art History after Postmodernism, eds. Norma Broude and Mary Garrard (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2005), 69-79.

[ii] Ibid., 64

Wonderful in-class assignment! Thanks for sharing, Izabel.