Teaching Art History and Writing II: SECAC Conference Panel Review

Many of us have overheard the frustrated professorial refrain, “My students should have learned how to write in their Freshman Composition class!” Perhaps some of us are even guilty of such utterances ourselves. But this myth, which Linda S. Bergmann and Janet Zapernick call the “inoculation approach” to writing instruction, creates a false separation between writing skills and content, between medium and message.[1] In fact, much art historical inquiry happens through the act of writing itself; formulating words, sentences, and paragraphs is a means of producing knowledge rather than simply expressing it. The ability to write articulately – along with visual literacy and critical thinking skills – is one of the distinct ways that an Art History education can foster a sense of agency. Accordingly, much is at stake in developing art historical writing skills at all levels of the curriculum, for majors and non-majors alike.

The panel Teaching Art History and Writing II at the 2018 SECAC Conference in Birmingham, Alabama, explored these issues. Similar to its sister panel proposed and chaired by Dr. Lindsay Alberts of Savannah College of Art and Design, the speakers approached the process of teaching art historical writing from diverse perspectives. Yet despite their differences, all shared the belief that Art Historical writing is an embodiedact. Whether considering questions of audience, creating interactive assignments, or fostering collaboration, each author foregrounded student agency as a meaningful strategy for enhancing their pedagogy.

Jenevieve De Los Santos discussed her use of creative writing prompts to scaffold toward larger visual analysis assignments with upper-level high school students and first-year college students. Her paper “Learning to Look, Learning to Write: Fostering Critical Thinking Skills in High School and First-Year College Students through Art Historical Writing” explored the value in breaking down the traditional visual analysis paper by allowing students to approach art works creatively without the stress of disciplinary jargon or historical context. Using Lev Vygotsky’s “Zone of Proximal Development” as a framework, she argued that creative writing assignments allowed students to first hone their close looking skills through prompts that focused on direct and detailed observation prior to engaging in more complex aspects of synthesis and analytical writing. Her presentation featured three sample prompts with three accompanying student-writing tasks. The first prompt “World Pile” asked students to generate a list of terms an image called to mind. In the second stage, students used their “Word Piles” to build poems, dialogues, or creative narratives. In “Creative Conversation” students, without historical context, created an imagined dialogue between group portraits or two figural representations in order to force students to build upon those initial exercises with subsequent, incrementally longer assignments. The third example asked students to create a “Character Profile” for a figure in an assigned unknown image, crafting a backstory and reflecting upon their emotional state as depicted in the art work. All three of these exercises connected to the final task of merging these observations into a comparative visual analysis paper.

In “Writing Art into the General Education Curriculum,” Janet Stephens asked; what about those students who will not go on to pursue an art history degree, or any other degree in the humanities? How can we use art writing to develop the transferable skills that justify the inclusion of introductory art history and art appreciation courses in the General Education curriculum? Those skills, writing but also critical thinking, effective communication, and the ability to come at problems from other points of view, provide lasting impact on our students. Stephens’ presentation created discussion of how to make writing matter to Gen Ed students, and shared strategies garnered from three years of teaching Art Appreciation. Specifically, it examined the success and limitation of her attempts to scaffold formal writing assignments onto classroom projects such as games and debates based on the idea that making the “stakes” of the formal analysis or research paper tangible to students will produce more effective and engaged student writing.

Cindy Persinger’s presentation, “Doing (Undergraduate) Research in Art History,” described how she scaffolded research assignments across the art history curriculum in order to cultivate a familiarity and enthusiasm for the research process in her students. Persinger’s desire to strengthen student writing in her upper-level art history courses prompted her to initiate a collaboration with her library’s art subject liaison at California University of Pennsylvania, Monica Ruane Rogers. Instead of waiting to address research in the context of a traditional end-of-term paper, she targeted appropriate research outcomes at various points in both her lower-level and upper- level art history courses. Persinger scaffolded research assignments across the curriculum, and the librarian mapped her objectives to specific information literacy outcomes. In this presentation, she focused on the semester-long Research Question Project that she assigns in her lower-level Introduction to Asian Art course. This series of assignments is unique in that students are asked to focus on the research process without producing a final paper, thus allowing them to develop several skills crucial to writing in art history, including: identifying a topic; developing and refining a research question; finding, reading, and evaluating sources; and writing a thesis and annotated bibliography. Students first identify a topic and draft a research question. Next, students find, read, and evaluate three peer-reviewed articles. Persinger has developed a list of questions that students must answer for each article. These “source sheet” guide the students through the reading and evaluating process. Students then re-evaluate their research question, and revise it as necessary. They then find two additional peer-reviewed articles, fill out the accompanying sources sheets, before completing an annotated bibliography and writing a short reflection on the process.

Finally, in “Two thumbs way up!”: Pedagogical Approaches to Creating Positive Results in WritingIntensive Courses, Naomi Slipp introduced Bloom’s Taxonomy and described the ways it has helped her be more self-conscious in upper-level art history course and assignment design. Using “17thand 18th-century Art” (taught in Fall 2017) as an example, Slipp described the syllabus, learning objectives, and prompts, and shared exemplars of student work in order to outline how she links course creation from the get-go to the positive results achieved at the end. Specifically, the six cognitive processes of Bloom’s Taxonomy – remembering, understanding, applying, creating, evaluating, and analyzing – are connected to Learning Objectives, which are linked with specific assignments, including examinations, in-class exercises, low-stakes homework assignments, and an article review and final research paper.

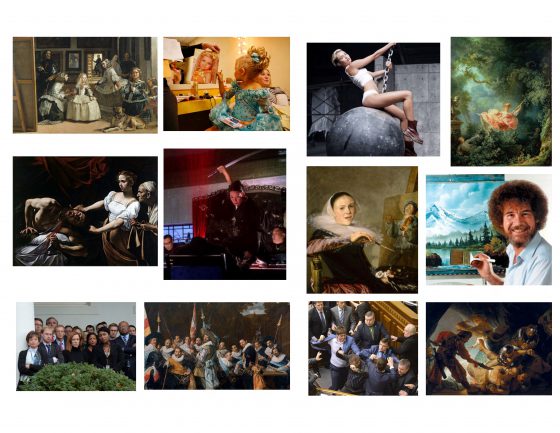

Slipp’s 12 homework assignments stimulated the most audience feedback. They included mini-research projects on global discovery, women artists, composers, and science, each of which build skills researching, summarizing, and using quotations and citations and also extend or supplement textbook material and lecture content. There were also creative projects, where students construct, model, or adapt a concept. Slipp shared examples of the latter, such as one where students pair a 17th-century painting with a contemporary image (fig. 1) and another where they restage an artwork photographically (fig. 2). The final homework acts as a capstone and asks students to conceive of an imagined exhibition, compile a dream checklist, and write an exhibition text and interpretive plan. Slipp concluded by arguing that due to the intentionality of her course construction and assignment design, students gained experience with each level of Bloom’s Taxonomy across a variety of assignments. This led them, in course evaluations, to describe how they “want to try harder, all of the time” and give these classes “Two thumbs way up!”

[Figure 1]

These same accolades could be applied to the Teaching Art History and Writing II panel as a whole. The presenters undoubtedly inspired the audience to “try harder, all of the time” in their own classrooms, and offered concrete strategies for doing so. Check out their resources below – we give them “two thumbs way up!”

[1]Linda S. Bergman and Janet Zapernick, “Disciplinarity and Transfer: Students’ Perceptions of Learning to Write,” in WPA: Writing Program Administration 31, no. 1-2 (Fall/Winter 2007): 124.

Thank you so much for sharing. This has arrived in my inbox at the most perfect time. This week my classes will be discussing art criticism in preparation for their first review. The strategies outlined in this article address the issues i have faced in the past where students are to inhibited and not confident to express their own views and therefore rely too heavily on external information. I definitely will begin my class with a Word Pile. Cheers