Bye, Bye Survey Textbook!

Over the past few years of teaching I have thought a good deal about how the learning goals I have for my art history survey students can be best met through the resources I ask them to engage with inside and outside the classroom. I’ve come to the conclusion that the “traditional” art history survey textbook doesn’t make the cut. Not the content per se, but the format.

Over the past few years of teaching I have thought a good deal about how the learning goals I have for my art history survey students can be best met through the resources I ask them to engage with inside and outside the classroom. I’ve come to the conclusion that the “traditional” art history survey textbook doesn’t make the cut. Not the content per se, but the format.

For a start, the books – pick any of the “big name” survey textbooks – are constantly going through editions for the purpose of making money (and improving images, text, etc – but really, baseline profit is the reason). The newest editions of any of them are well over $100. This is a great deal for any student to invest in, and a waste given that many of the students are going to use the books as giant and expensive coffee coasters before trading them at the end of the semester. Pearson, Stokstad’s publisher, did put together “My Arts Lab” which sourced materials from the web and synched them with their own to provide a “multi-media” experience for students that could be set as homework by the instructor. There’s also the “less expensive” $60 online textbook versions. None seem like thrilling alternatives.

Then there’s the manner in which the content is presented. I love flipping through my copies of Janson and Stokstad. The images are great and it’s a useful way to understand chronology, to check dates, to see images in comparison. But reading survey textbooks? They’re not compelling. They’re not rich in detail (too much to get through, no time for lingering analysis!). They’re also, emphatically, not the type of art history I want my students to be writing. So why would I assign them as reading?

The very first semester I taught the art history survey, I was handed a copy of Stokstad’s Art History, Volume II as if it were the bible. I ended up spending far too many nights reading it word-for-word into the wee hours, and then trying to put together a lesson plan that summarized the information. Naively, I also asked my students to read sections of it before each class. They hated it. They didn’t do it.

The second semester, things had to change. Or more specifically, the textbook had to. I ditched it. The textbook devoted twice as much space to the history of the Western world than anywhere else, so I couldn’t teach the truly global survey I was required to if I used it anyway. It also didn’t seem ethical to continue to force students toward something that was so evidently unappealing. As their instructor, it was my duty to work to find a more inspiring model. How could I expect my students to by psyched to read something that I didn’t think was great?

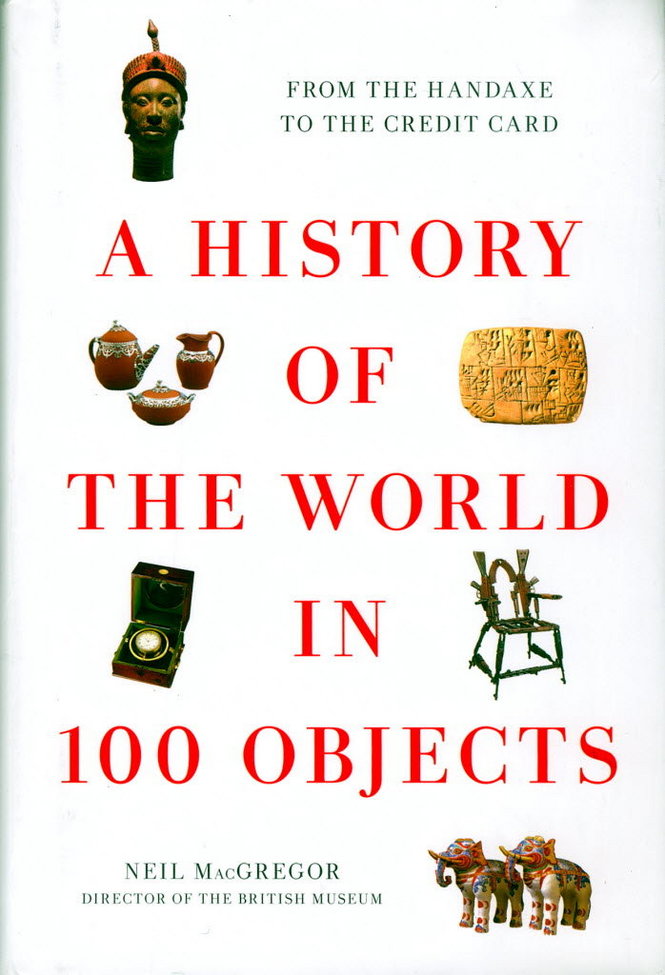

I had been listening to BBC Radio 4’s wonderful A History of the World in 100 Objects (later aired on PBS in the States), written and narrated by the Director of the British Museum, Neil MacGregor. He is such a compelling writer. Selecting 100 objects from the British Museum, MacGregor makes each into a chapter that starts from a very specific focus – the object itself – and branches out to weave a beautiful web of history, economy, society, memory, and politics. Selecting chapters from the book became the basis for the reading I wanted my students to do outside of class. They would read about the object – say the coin portrait of Alexander the Great – before our class on Ancient Greece. Then, we’d begin the lesson with the object up on the screen. “What do we know about this object?” I’d ask. “What can it tell us about Ancient Greece?” Students feel excited – they know! Because many of them have done the readings! Because the readings are no more than 4 pages long, and written like a radio conversation. Students have opinions about what MacGregor thinks – and how he writes.

I didn’t want to rely on only one “voice” though – it would be too close to the model I was trying to escape. When I was a student the survey was split up into sections and team-taught by specialists in each field. Without recourse to said specialists to come into my survey in person and lecture, I decided to annouce to my classes that each week we would hear from experts in the field in which we were studying. So that meant that either in class, or for homework, instead of reading Stokstad on Prehistory they would watch Mike Parker Pearson talk about Stonehenge. Pearson has been excavating there for over 20 years and is world-renowned for his archeological work. It seemed like he’d be a compelling source. He was. There’s a point where he splutters excitedly over several shards of prehistoric femur: “this is the most important discovery OF ALL TIME.”

While any of us outside the confines of Stonhenge research might beg to offer our own specializations as the most important discovery of all time, it’s far easier to enthuse students with this type of resource that a survey textbook. The neat paragraph of standard interpretation is easily given in post-film discussion. What’s more, by having students watch the first 15 minutes of his PBS Nova program they get to see Stonehenge in all its 3-D glory.

Alongside Pearson, I use History Channel excerpts to introduce the Egyptians, Nigel Spivey to introduce contrapposto (watch from 5 min – 7min), Engineering an Empire to talk about Justinian’s Byzantine bloodthirstiness and Chinese hydraulic prowess. Nancy Ross has written convincingly about how to use pop culture excerpts to get students engaged, and Smarthistory offers great links to further resources for every part of the survey that subvert the boredom of required reading. The Met Museum has amazing, free online resources, from the Timeline of Art History, to Connections and 82nd and Fifth.

These types of resources are free, can be easily added and subtracted from, and are in formats – text, video, audio – that speak to the different strengths of students.

I’m arguing for the end of the compulsory survey textbook, and I’m certainly not the first (or even second) person to do so. There are textbook-alternative resources for sections of the survey on the AHTR site under “lesson plans” and we’re adding more all the time. Post below if you’re willing to share your favorites – or if you disagree and can make a case for keeping the textbook on the syllabus.

I don’t think that there are any compelling reasons to continue to use a traditional textbook in art history. Like you said, they are overpriced, contain little detail, use inaccessible and/or uninteresting language, all those images can be found online, and HEAVY. Everyone hates lugging those things around! I stopped using them 18 months ago and I haven’t looked back.

It took me a long time to come around to this way of thinking. I was really wedded to the idea that the students needed a BOOK. An honest-to-God b.o.o.k. I have been worried that too many of my students do not use books for either the courses or for pleasure (one bragged to me that he only owned one book – the one he had had to buy for my class). But a fact of the matter is that the survey cannot accomplish what I would like in the classroom. Macgregor also provides a model for them when writing their own short formal analyses or the results of their research projects. I still put the surveys on reserve in the library and several of my students use them when prepping for the exam. The books contain a very useful amount of historical context. But for the reasons outlined by Michelle above, I will not be requiring them anymore.

I love this “I didn’t want to rely on only one ‘voice'” — mostly because it’s my main reason for wanting to ditch all the textbooks.

I’ve experimented with teaching classes textbookless for about 3-4 years now, and I often revert to the text because of the labor involved in creating an alternative. As a contingent teacher it’s always been hard for me to find the time and energy to create the alternative, and I worry that putting too much energy into doing that reinforces the (often white often male) voice of authority that plagues the discipline. If I’m spending my limited time organizing and reorganizing teaching materials rather than producing scholarship that eventually gets into the textbook(s) can I ever be an authority in the same way as those who don’t do that are?

SUCH a good point to make Renee, and apropos of everything that is being talked about just now in terms of how our field/tenure committees value digital scholarships/efforts/publishing in general. I hope that this site goes some way to remedying the time consuming nature of moving away from the textbook, and making the alternatives visible.

Marie Gasper-Hulvat is going to write in May about some of her ideas on such resources. As I mention above, Smarthistory has them too. I think we need them organized with instructions for students, or digested so we as teachers know exactly what each resource contains and how to make it a useful tool without having to go through the process of watching every second of the video or reading every word of an online essay before the semester starts.

We have many such links in the lesson plans on the site already, but it seems they’d be best listed in a one-stop “textbook” (I hate that word, is there another term?) page. We’re going to produce an amalgam of all the resources that people will share and that we use/know about (ie. peer-populated, collaboratively authored) in the form of an online “textbook” of resources per survey unit that teachers can simply copy and paste, and use for their classes from summer 2013. We’ll draw from Smarthistory, the History Channel, PBS, the BBC, Museums – and format them in a week by week “reading” list germane for use in a course syllabus.

That way, no more reinventing the wheel. And, they can be added to and kept up to date via the comments section on the page.

A few years ago I really noticed the difference in the way Stokstad introduced Christianity and Buddhism. Buddhism was explained in some detail, Christianity was not. It was taken for granted that the majority of students using the text would already be well-versed in Christian catechism. Of course, this is certainly not the case within CUNY. Moving away from the text provides the opportunity to reach all of the students in a thoughtful and meaningful manner.

And we need ideas to replace the word “textbook”!

I love the idea of having multiple voices and multiple media types for the students to learn from. I worry about throwing the baby out with the bathwater, though. As much as these sources are engaging and compelling, I find that my students are coming to class with almost no concept of the development of Western or world history. For all its faults, I think the textbook can provide a clear timeline and better continuity than multiple, mixed sources. Maybe I’m too conservative, but on some level I think that homework has to be work, not entertainment.

Can I play devil’s advocate here Danielle (and offer more fuel for discussion as I’m really enjoying teasing this out through the great comments!). You raise a very legitimate concern we heard a lot at CAA about really offering students a foundation they lacked by using the textbook. But……

a) What’s more discontinuous and messy than history? And what better way to have students figure that out than have to synthesize the views of different authors and sources, rather than one continuous voice? Might the many-voice model raise their criticality toward sources (& offer a transferable skill for other college endeavors)?

and

b) Would using a “course textbook” work better/be more valuable in a class where students were electing to take the course, rather than being forced to in order to fill a requirement? I teach mostly the latter art history survey student, but I can imagine the former being more excited to have a course textbook. Is that true of anyone who has elective art survey students?

I like the idea of pulling together a free and open digital textbook with all of the materials of a textbook, but where many of those materials are links to good info. Like a larger, more complete version of The Art History Flashbook http://arthistoryflashbook.blogspot.com/ .

I also think that students can be entertained and learn at the same time. The two are not mutually exclusive. If I think of exciting moments of research and learning from my own past, a lot of those moments felt dramatic and entertaining. Art history isn’t a dry subject. It doesn’t need to be presented in a dry manner.

Loved the ideas that came out of that THATCamp session!

Can we call it a flashbook then? Or as Marie Gasper-Hulvat has called it, a “sylla-book” where each part of the syllabus comes complete with links for homework? I want to add guided question sheets so students know what to bring to the classroom as “talking notes” for discussion/have guided ways to work through the materials and know what to look for.

Regardless of the name, look out for the first prototype in mid/late May, in time for summer courses – and feel free to suggest/offer materials before then or edit/add when it’s up.

Sure. I also like the term sylla-book!

I guess I’m playing the devil’s advocate a bit as well. I haven’t given up the textbook yet… I’ve thought about it and deliberated, but haven’t been sold. I do use a lot of video clips like you’re suggesting, but I am still deciding what I think is the right balance.

I agree that history is discontinuous and messy… but are survey students ready to put together that narrative for themselves? I don’t mean that pessimistically, but you have to crawl before you can walk. We had to go through Modernist hegemony to arrive at Post-Modernist plurality. Likewise, I feel like the students I teach are still learning the addition and subtraction of history and aren’t quite to advanced algebra yet. I want to complicate things a little bit for them, but I still feel like some narrative of continuity has to be developed. There is just too much information teaching a caves-to-contemporary survey to nuance it all, especially when most students can’t identify major historical periods or even geographical regions sometimes.

And I agree! Art history shouldn’t be dry! I try in my teaching to always relate the material to ideas/objects from contemporary (visual) culture. But I still think it should be rigorous. Great moments can come from struggling with material and conquering. If the process of assimilation is always easy, there is less of a sensation of accomplishment. Don’t get me wrong, I don’t think art history should be torture! But I think there should be balance.

I do worry a lot about the cost of textbooks. So far I’ve recommended the students get older editions (which can usually be purchased for about $30 online) if it is a great concern. As far as assigning them to students for whom the class is optional, that doesn’t really change the equation in my mind. If anything, I would feel more comfortable assigning a variety of sources to art-historically minded students because they might already have the foundational knowledge a textbook provides.

I think that there is a misconception out there that using a textbook equates to rigor or even that it presents a coherent narrative of Western Art. I used to use Gardner’s Art Through the Ages and it is was exceptionally poor at relating ideas across chapters. It included so many works of art that it lacked depth. It did contain a lot of information, but my undergrads are not good at picking out the important things and retaining that information. I think that that is one of the great strengths of Smarthistory and a number of other online resources. As far as rigor goes, I feel that I can expect more from my students because the homework is more accessible, both in terms of being free and online and also in terms of the kind of language used to discuss art. I would say that there is a directness that is present in online resources that is not present in traditional textbooks.

All good points, Nancy. I suppose, on some level, I am a sucker for all the glossy images and the attempt at encyclopedic inclusivity (as archaic as that is). And I can’t getting around wanting to have a central reference text. Maybe as I explore the increasingly diverse (and well-developed) on-line materials that will change. For now, I do see some good in having a textbook.

I love the Metropolitan Museum resources; also the Tate Channel; SmartHistory is great visually but the videos can be a bit basic in their commentaries. Don’t forget the OU have some superb free resources, e.g. on the Venetian Renaissance. I have collated a few resources for students here: http://www.hotelalphabet.com/the-library-art-writings.html

My main problem with survey text books is they are still so lazy when it comes to researching and presenting the work of female artists (especially if you go back to the Renaissance)

The reminder about the OU is a great one – I’ll definitely be going to take a look again. I know they have some really super resources on Modern Architecture. Thank you for sharing the link to your collated resources!

I am really enjoying this discussion and the debate – the idea of leaving behind the textbook (Gardner’s in our case) is thrilling and terrifying. I am wondering if any of teachers who have opted to drop the textbook have encountered issues with credit transfer for students moving on to other schools? This is an issue we encounter as our program is just two years, and many of our students transfer to 4-year schools.

Great discussion! I thought I’d share some feedback I got from my class last semester after ditching the textbook (Arneson) in my modern art course–70% of my class preferred on-line resources over textbooks. In addition to podcasts, videos, and lecture captures, I assigned overview texts on The Art Story, the Met’s timeline, and Oxford Art On-line, which were more closely aligned to the content I was able to cover in the course.

They cited as their reasons the expense of books, environmental concerns, and one felt the on-line material might be more current. Re: the interactive media, they liked the ability to pause and replay points they may have missed, and to focus on material privately at home and at their own pace

Students favoring textbooks said they missed the ability to highlight relevant points, easily refer to/access specific information, and having clearly defined boundaries about what information to study. Both groups noted that they were easily distracted by links to other points of information.

This suggests to me that students (like many of us) are struggling with how to adapt traditional study techniques to their use of on-line resources. I don’t really buy the whole digital natives thing based on my current students, so we need better systems in place to teach students these skills.

This semester I did an in-class workshop the first week of class focused specifically on the technology we’d be using. We discussed how to engage critically with podcasts/videos and exchanged various note-taking practices for on-line materials. I was shocked to learn that about half of my class of 35 prints out everything off the web they are assigned!

Virginia, your comments are super insightful, thank you for sharing. Again, I’ve been rmeinded of another really great resource by your comment – Oxford Art Online is somehting I use all the time, and I much prefer its detailed biographies and historical overviews to the lack of information from a survey textbook.

Your discussion with your class over how best to appraoch online resources sounds like a really valuable step to take. Do you have a planned approach for this? A lesson plan? A handout? Or is it much more of an open-form discussion? If you have any plan, would you consider sharing it here, and us using it on the site as part of the online sylla-book/flashbook we’ll post to the site?

One thing I learned is that your university’s library subscription may have limits for the number of concurrent users of Oxford Art On-line. I had the class divide into 8 small groups, which exceeded our campus limit and forced some, um, improvisation on my part. Good idea, gone wrong, and I gained a great lesson.

Likewise, the exercise taught me that showing a short smarthistory video in class caused students to go into passive movie-watching mode. When I commented on their lack of engagement, many of them said that they get more out of these resources when watching them alone on a computer (usually with headphones) because they can pause and replay as needed. Excellent stuff to know!

Of course, I’ll share! The lesson details are outlined in the “How To Study On-line” assignment on my website:

http://vbspivey.wordpress.com/assignments/assignment-ideas-and-rubrics/

This is brilliant stuff, thank you Virginia! Really looking forward to your post in a few weeks!

It would seem to me, that any attempt to teach histories at the introductory will encounter the same problem: namely, a need for a coherent narrative that students can latch onto and understand. As one who teaches the survey (and upper-level courses) at the least high-performing of the CUNY senior colleges, I am constantly amazed at the lack of basic factual information grasped by the students. Is there a way set up a compelling narrative, but still present dichotomous histories? I feel as though I am trying to show my students Rashomon, but we only get through two-thirds of the film.

“Is there a new way to set up a compelling narrative, but still present dichotomous histories?” I think you have lain down the gaultlet in one sentence randall. If you have enough ideas to write a blog post, let us know – if not, I think the question still stands and we’ll do our best to keep throwing it out and seeing what comes of the conversation……

[…] while back, I wrote about how I had ditched the art history survey textbook. A healthy discussion ensued in the comments section about whether or not the art history survey […]

[…] in March, Michelle Millar Fisher told us about how she has ditched the art history survey textbook in her courses, replacing the traditional paper-based book with free online resources. While I had done a […]

[…] a similar argument in her blog post, Bye, Bye Survey Textbook! Michelle Miller Fisher […]

As a student in art education I have struggled with this class. I am actually required to take 4 art history classes for my degree. We have to use the book in discussion, Stostad. This book, although informative is very difficult to actually read. I honestly have a extremely hard time staying awake for the readings. I have done everything I can think possible to learn this information but this type of class constantly is taught in lecture halls for over a hour. That is a long time to sit for a book that’s being summarized by the instructor for you. Through my time in school I have enjoyed that teaching a subject should not only be taught one way. This class however, isn’t interesting and it’s required. I’d like it to be more engaging and not just be a textbook recited to me. Fellow classmates have said the same things. In the arts, one of the best things are seeing and learning about all the different types. I can learn more about the subject through small projects and discussions that tests, quizzes, and a research paper. Learning is supposed to be taught through differentiated instruction. That’s what we are taught when learning to become a teacher. Yet, when you take classes such as these it’s taught only one way. Summarization of the textbook. I believe that as future art teachers we would learn more if we were give a chance to think outside the textbook. Every other class is a hands on approach to learning; why does it have to stop when it comes to these particular classes?