Chinese Art Before 1300

First Things First...

To begin, ask your class to describe their impressions of what Chinese art is–most likely, their response will be a narrow version that has been digested and transformed by Western culture. China is an immense geographical region whose borders have grown and shrunk over the centuries, containing a diverse group of ethnicities, religions, historical ruling parties, time zones, and ecological environments. The whole concept of “Chinese” art, however, is really a notion that only began in the nineteenth century and is a term that can encompass a wide variety of heterogeneous practices. Yet, the broad scope of this topic can be divided into three areas of artistic expression, including works of art created for burial practices, Buddhism, and the courtly cultural elite. At the start of the lesson, review the basic tenets of the three major worlds of thought that influenced Chinese culture during this period: Confucianism, Daoism, and Buddhism

Since their conceptions, the philosophical systems of Confucianism and Daoism have worked hand in hand with Chinese culture. Confucianism developed during the Zhou dynasty, in which Confucius was born c. 521 BCE . A non-metaphysical and humanistic system, Confucianism is about man’s place in society, a society that can be perfect if people conduct themselves perfectly. It is also a conservative and hierarchical system, which places men over women, and the ruling class over peasants, without any chance for upward social mobility. Seemingly at odds with Confucianism, Daoism’s origin is attributed to Lao Zi who lived during the fifth century BCE and is thought to be the author of the Dao de Jing (the Book of the Way and Its Power).

Where as Confucianism is about man’s place in society, Daoism ignores society and, instead, concentrates on man’s relationship to the natural world–the Dao–in which man’s goal is to live in perfect harmony. All natural phenomena can be explained by the yin and yang, opposing forces in nature that blend together in perfect harmony. The yin is female, soft, slow, cold, etc. and the yang is male, hard, fast, hot, etc. During the Han dynasty (206 BCE-220 CE), Daoism began to incorporate magical rites to help reach followers reach immortality; deities also play a role in these rites and have eventually become part of Chinese popular culture.

Buddhism came to China in 65 ce. and introduced presuppositions that differed from the dominant Chinese philosophies. Buddhism operates with the notions of samsara and karma, the belief that life is an endless cycle of rebirth and deeds from past lives determine an individual’s place in this life and future lives. Because Chinese culture already had established concepts of the afterlife, these new ideas were not readily accepted. The influence of foreign rulers was needed to bring Buddhism into cultural prominence.

Background Reading

Content Suggestions

The following list includes Chinese art within the contexts of the tomb, Buddhism, and art of the courtly elite within an hour and fifteen minute session:

- Funerary Jar, Banshan phase, from Gansu, third millennium BCE

- Yu, Shang dynasty, eleventh century BCE

- Terracotta Army, tomb of the Emperor of Qin, (d. 210 BCE), from Lintong near Xi’an, Shaanxi, Qin dynasty, 221-207 BCE

- Funeral Banner from the Mawangdui Tombs, Changsa, c. 168 BCE, Han dynasty

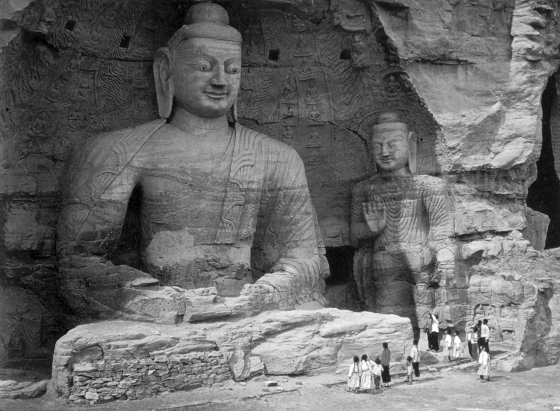

- Colossal Buddha, cave 20 at Yungang, Shanxi, c. 460-93 CE, Northern Wei dynasty

- Shakyamuni and Prabhutaratna, 518 CE, Northern Wei dynasty

- Horse and Female Rider, Tang dynasty, seventh-eighth century CE

- Guo Xi, Early Spring, early eleventh century CE, Northern Song dynasty

- Ma Yuan, On a Mountain Path in Spring, twelfth-thirteenth century CE, Southern Song dynasty

- Music, Six Persimmons, thirteenth century CE, Southern Song dynasty

The earliest cultures in the Henan, Shanxi, and Shaanxi Provinces along the Yellow River in the “heartland” of China, developed during the Neolithic period, in which civilizations produced utilitarian objects with decorations. The earthenware Funerary Jar, decorated with slip, is one such example found in the context of a tomb. Scholars know that Neolithic earthenware pottery was used for daily life and funerary purposes, but beyond that, not much information about this jar or its culture exists. Scholars do not know how it was intended to serve the deceased in the afterlife. A good explanation of the chronological phases of Neolithic pottery can be found on the Princeton Art Museum’s website.

Bronze vessels, produced during the Bronze Age after the Neolithic period, characterize the Shang period (c. 1500-1050 BCE) culture, which had the most highly developed bronze technology of the ancient world. The Shang kingdom was a single political entity ruled from a sequence of capitals in the present-day Henan province. Although it was surrounded by rival states, Shang culture spread beyond the Shang kingdom. The site of Anyang was the center of Shang ritual culture from 1300 BCE until the end of the dynasty in c.1050 BCE. Here, bronze was used for weapons, chariot fittings, horse trappings, and for vessels. Bronze vessels were used during special banquets in order to honor deceased members of high society–in addition to human and animal sacrifices. Therefore, all of the deceased needs were met in the afterlife. Nobles performed these sacrifices and rituals to insure their success by appeasing their deceased ancestors.

The making of bronze vessels suggests a stratified society and urban centers of production. A good interactive site explains how bronze vessels from the Princeton University Art Museum were made. The Yu is a bronze wine vessel that was used during great banquets of lavish food and drink to honor ancestors. The vessels were then subsequently buried with other members of the elite–the higher a person’s rank, the more objects buried with them. Shang dynasty bronzes, covered completely with decoration, utilize many zoomorphic motifs with surfaces that usually display horror vacui. One interesting motif found on the Yu, the taotie (usually translated as “ogre”) mask, is a symmetrical composite zoomorphic design. It is a full-face mask that can be divided down the nose, with both sides depicting one-legged, bird like creatures. The exact meaning of the taotie is unknown, but because it appears so often on early Chinese vessels, it is apparently an auspicious motif. More information on the Shang dynasty can be found in the Teacher’s Guide created for a past exhibition called “the Great Bronze Age of China” at the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

The first emperor of China, Emperor Qin (reigned 221-210 BCE), was the first to unite the empire and the first to give himself the title of Imperial Sovereign. He was anti-Confucian and is thought to have burned its books and killed its scholars via live burial. He also standardized weights, measures, and writing systems, built roads to move his massive armies, and started building the Great Wall. Under Qin’s rule, this period was the first time China was thought of as a cultural entity.

A farmer accidentally found Qin shi huang di’s tomb in 1974. Since then, a thousand terracotta soldiers have been uncovered in military formations, with seven thousand soldiers estimated in total. The Chinese government is reticent to do more excavating as the terracotta soldiers can easily break (at least that is the official statement). The soldiers are all life size from five to six feet tall and originally, they were painted to enhance the life-like appearance of the figures. Although terracotta is not a luxurious material, the massive scale of this tomb’s construction was incredible, involving hundreds of workers who were deployed for this operation. Hundreds of tons of firewood and many massive kilns were needed to fire the figures, created by a modular system of prefabricated parts: a plinth, a set of legs, a torso, two separate arms, two hands and a head. To increase the number of unique combinations, there were three plinth styles, two types of leg sets, eight torsos, and eight heads. The hands were composed of smaller molded parts and the facial features and hair were customized per figure. The consequent variety of soldiers with life-like appearances helped better fulfill their roles as guardians of the master in the netherworld. The emperor’s unprecedented rule made construction of this massive tomb possible, and helped to immortalize him in history for generations to come.

In addition to this elaborate tomb for the First Emperor, other elite members of the populace were preoccupied with their immortality during the Han dynasty (206 BCE-220 CE), which can be evidenced in the Mawangui tomb complex. This preoccupation caused myth, miracles, and magic to be incorporated into Daoism, which previously had emphasized living in harmony with nature. Mawangdui has three tombs in which archeologists have found several artifacts–including many surviving Daoist and Confucian texts, mainly in Tomb 3. Since Confucian and Daoist texts were privileged property of elites, they were buried with them. The Funerary Banner from the Mawangdui Tombs was found in Tomb 1 draping the inner coffin of the Marquise, the wife of the Marquis of Dai, the chancellor of the Kingdom of Changsa. This banner is often considered to be the precursor of the hanging scroll, prominent in Chinese culture after the eleventh century, and can be interpreted in terms of Confucianism and Daoism.

The banner has three levels: the upper level represents the heavens, the middle the earth, and the bottom the netherworld. The upper level depicts a sky filled with mythical creatures that recall Daoism mythology: a raven in the sun, a toad on the moon, and celestial dragons fly through the heaven (as they are explained in Daoist texts). The middle section shows Confucian scholars bowing down to the elderly, well-fed Marquise with her female attendants. This section uses hieratic scale to portray the hierarchy of Confucian society, meaning that the most important figures are the largest. The lower portion of the banner depicts men performing rituals with bronze vessels, a tradition that developed during the Shang dynasty (c 1500-1050 BCE) to honor the deceased. This tradition is clearly adapted here as a Confucian tradition: Confucianism stresses respect to elders, ancestors, and a hierarchical society. A serpentine beast supports the netherworld, which is another visual interpretation of Daoist mysticism.

Originally a people of Turkic origin from the Russian steppes, the Northern Wei (383-535 CE) rulers conquered China in the early fifth-sixth centuries CE and were the first to widely spread Buddhism. The Northern Wei rulers were great patrons of Buddhist art and expanded the number of monastic establishments to 13,272, but there were some periods of Buddhist persecution under their rule. An anti-Buddhist imperial decree was established from 444-451 CE, reversed upon the death of its advocate.

After this decree was reversed, Tanyao, a Buddhist monk, suggested the construction of the Buddhist site of Yungang. Often called the Tanyao caves, the site has five caves which house five colossal Buddhas, which may represent and glorify the five Northern Wei emperors up until that time. The construction of these caves was purposely meant to outdo the contemporary rock-cut architectural sites of India and Central Asia. Since Tanyao was trained in Kashmiri Buddhism, the five Buddhas could also represent the protection of the Wei state based on the cosmology of his Kashmiri Buddhist sect. Although information on the Yungang site is limited, scholars do know that after initial funding given by the court, it was also funded by other parts of society. Many families pooled their resources together, as evidenced by inscriptions at the site that bestow blessings on them. The variety of styles in the carvings suggests that many different workshops and hands worked at the site.

A great example of private art during this period includes the sixth century altar depicting Shakyamuni and Prabhutaratna. Commissioned by groups of aristocratic families, gilt bronze altarpieces would have been part of the main altar in Buddhist temples. The figures are depicted in an elongated manner with little corporeal reality and their drapery is emphasized, with sharp “saw tooth” points carved into the bottom of their robes. Their heads are adorned with pointed and flaming halos, an indicator of divinity and a hallmark of the Northern Wei style of the sixth century CE. The iconography of this sculpture represents a story in the life of Shakyamuni, the Historic Buddha, and his encounter with Prabhutaratna, a Buddha of the remote past. In the story, while Shakyamuni gives a sermon on the Vulture Peak, a miracle occurs and Prabhutaratna emerges from his stupa (reliquary) to listen and the two Buddhas sit together. The two figures are identical in appearance because conceptually they are the same: all mortal Buddhas live the same lives and give the same teachings.

The Tang dynasty (618-906 CE) was a period of increased global contact since its capital at Chang’an was an active trading center on the Silk Route. Due to this internationalism, multiple religions and art traditions were practiced in the capital. Tang upper class tombs were decorated with ceramic sculptures, many of which portray images associated with wealth. The tomb ceramics were cast from molds and assembled in sections, which made construction of the objects quicker and more easily available for tomb furnishings. In ceramics, the horse was a popular subject as it suggests wealth, trade, and can be associated with the military. Projecting these values, the Horse and Female Rider, for example, is typical of the Tang’s famous three-color glaze technique called sancai. The glaze contains lead and its ability to drip during the firing process was a desired, decorative effect. The female rider is shown wearing a close fitting garment that was especially useful when riding through the desert.

After the Tang, by contrast, the Northern Song dynasty (960-1127 CE) was a period of great unrest, constantly threatened by invasion. Despite this underlying conflict, this period also saw the establishment of the professional Imperial art academy. Artists, part of the cultural elite, held civil service jobs, which allowed them ample opportunity for artistic pursuits. Guo Xi served in the Academy and his painting, Early Spring, is considered to be a masterpiece of Northern Song dynasty painting. Utilizing the mountain and the water (called shan sui) as the yin and the yang, the painting is believed to represent a Daoist Paradise. In Early Spring, the mist obscures a solid mountainside, as if the mountain does not exist. Guo’s use of empty space is just as important as the subject matter, balancing the composition. This painting is over five feet tall, yet it still remains an intimate artwork since its detailed brushwork requires the viewer to be up close. For a detailed exploration of this image, the University of Washington’s site about Northern Song landscape painting is an excellent source.

The formats of East Asian painting differ greatly from those of Western art. Early Spring is a hanging scroll painting, therefore it can be rolled up and removed easily depending upon the wish of the owner. Western paintings are not usually moved as easily. The hand scroll format is viewed in small segments with only up to three people at a time. Album leaves, the third major format, are about the size of notebook paper and are meant to be viewed from up close. Please refer to Maxwell Hearn’s video about hand scroll viewing explains the intimacy of the art form and more.

The Southern Song dynasty (1127-1279 CE) is thus named because the capital was moved from Kaifeng in the North to Hangzhou in the South. The Jurchin Jin dynasty had taken over the northern lands. The geography and climate in the South greatly differs from the North, including much more water, rolling hills, and valleys. Courtly painters in the Song Dynasty, like Ma Yuan, favored the album leaf format. His On the Mountain Path in Spring is the quintessential depiction of the life of a gentleman scholar. Ma Yuan depicts the scholar figure in hieratic scale, relatively larger than his servant (who carries a musical instrument) in order to show his importance. The leaves on the tree are just beginning to bud and birds have taken flight, representing the beginning of spring. The artist included a poem by Emperor Ningzong in the upper corner of the painting, demonstrating the interconnectedness of poetry, painting, and calligraphy in Chinese art. Calligraphy, in fact, is considered the highest art form and painting is the lowest. For a closer view of this painting please refer to the Southern Song landscape page from the University of Washington. James Cahill also devoted a lecture to On a Mountain Path in Spring, which is available on his website.

Another artist in the Song Dynasty, Muqi was a Chan Buddhist monk, hence a “non-professional” painter. Chan Buddhism was brought to China at the end of the twelfth century CE and is a direct and brief doctrine that emphasizes mindfulness, meditation, and the immediacy of experiences. Chan is commonly known as Zen (after the Japanese word for Chan) in the West. Muqi is an exponent of the “spontaneous mode of painting,” a type of painting that requires great brush skills, yet looks effortless. The persimmons in Six Persimmons look as if they are floating on the surface of the paper, their stems made out of perfect calligraphic brushstrokes. Since the Southern Song dynasty Chan Buddhist painting style is favored in Japan, the Six Persimmons is held in the Daitokuji in Kyoto and is rarely seen in person. James Cahill also dedicated a lecture to Chan Buddhist painting which is available on his website.

At the End of Class...

Further Resources

Smarthistory on Imperial China