Learning and Unlearning: Using hands-on Bauhaus exercises in art history classes

At its heart, the Bauhaus – with all of its far-reaching design goals and wide-ranging art historical influence – was a school. From 1919 to 1933, creative women and men went to its various buildings (first in Weimar, then Dessau, then Berlin) to learn modern ways of making things. So, of course, there were countless Bauhaus

assignments related to developing students’ technique and awareness of materials and methods.

[Josef Albers’s Preliminary Course at the Bauhaus, 1928–9]

For those of us teaching the history of art or design, some of those lengthy technical explorations may not be practical to replicate – or directly relevant to our curricular goals. But, luckily for us, the Bauhauslers also experimented with quick, hands-on activities, imbuing them their underlying beliefs in forging a new visual language and a new way of life.

Adapting Bauhaus exercises in my art history courses has not only enlivened long class periods, but kinesthetically engaged students in learning art historical content I might otherwise (or additionally) deliver through lecture. My aims with these multi-modal lessons are to communicate essential Bauhaus philosophies, to introduce or reinforce knowledge of the Bauhaus visual language, and to link Bauhaus pedagogy with the school’s socio-political goals.

A few practical notes:

- These activities can take just a few minutes or over an hour.

- Most are geared toward small classes, but I have used some in large lectures.

- They all use basic, fairly “clean” materials: I have a stash of scissors, glue sticks, colored markers and pencils that students may use but some of the exercises do not require any materials or prep time.

- I do not use all of these activities in any given semester but will pick one or two depending on the dynamics of the group or my content goals.

Warming up to Unlearning

Many Bauhaus instructors – with Johannes Itten as a key example – believed that traditional divisions between the applied arts and fine arts should be erased and, furthermore, that the conventional thinking that led to the first World War needed to be surmounted. To that end, instructors involved students in “unlearning” or “deschooling” exercises that encouraged students to look at the world anew.

Some of these lessons stretched on for months, in scaffolded or iterated explorations of material and form. For my purposes, I have adapted some of the shorter activities including:

- Beginning class with stretching or breathing, whatever students feel comfortable with. (I must confess that I have not yet been bold enough to lead students in Itten-style chanting.) Itten intended these activities to open up the mind and senses.

[Students in one of Johannes Itten’s “unlearning” exercises at the Bauhaus]

- Quickfire drawing exercises that engage students in a kind of automatism (preceding Surrealism) that was intended to directly connect the hand with the mind and, again, to open up possibilities beyond received, conventional ways of doing things.

- For example, I will call out one emotion (to which students immediately respond with a gestural line or mark making), followed by a contrasting one.

- Or I will ask them to create any spontaneous mark, then another one with a contrasting direction, texture, width, value, etc., then another and another. And speaking of contrasts…

- Discovering Contrast and Harmony

Itten and others believed that a universal visual language could be forged by discovering the underlying contrasts and harmonies of our world. Josef Albers, who was both a student and teacher at the Bauhaus, also believed that art and design could be understood and created through oppositions of light, color, texture, material, line, emotional tone, etc.

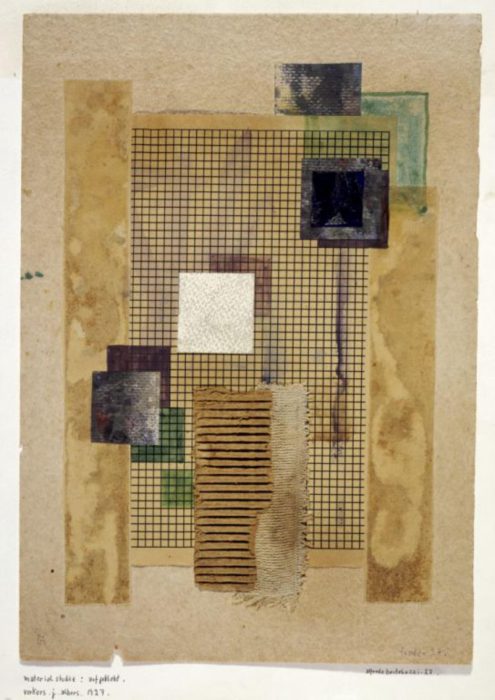

Abstract, found-material collages or assemblages

This was a common Bauhaus preliminary assignment and is easily adapted for the art history classroom:

- Give students 5-10 minutes to scavenge for contrasting materials in their bags, in the classroom, or beyond (depending on how widely you want them to roam).

- Emphasize the sensory-corporeal focus of Bauhaus pedagogy by asking them to strongly consider texture in addition to any other formal elements.

- After gathering materials, students tear or cut materials into simple abstract shapes and/or arrange them on or next to each other, looking for maximum contrast or harmony.

- You can provide scissors, glue sticks, and white paper (as a surface), or they can simply focus on layering and composing.

[Monica Bella Ullmann (later Broner), Contrast Study with Various Materials, 1929–1930]

[Alfredo Bortoluzzi, Material Study, 1927]

,

Josef Albers’ simultaneous contrast exercise

I am extremely fortunate to work at an arts college within a program that emphasizes collaboration. My colleague, Ilana Zweschi, a drawing and painting instructor, has been kind enough to guide my students through Josef Albers’ color theory exercises. These in-depth exercises could be easily adapted to simply emphasize the process of experimentation and the observation on how color behaves.

- Students begin by choosing two small rectangles (approximately 1 x .5 inch) of the same color.

- They experiment with different backgrounds of larger paper (approximately 7 x 5 inch) to create a visible contrast between the small pieces of color.

- Students can glue down their findings on white paper, if desired.

- Extension Option #1: Students can articulate why this is happening by applying terms such as value, saturation, temperature, simultaneous contrast, etc.

- Extension Option #2: Students can take the more challenging next step, which is to choose two small rectangles that are different in color and experiment with backgrounds to reduce the differences.

[Students at Cornish College of the Arts experiment with Josef Albers’ Simultaneous Contrast exercise, 2017]

- Finding Fundamental Forms and Colors

As the Bauhauslers developed a unifying, universal visual language, they converged on primary colors, abstract shapes and forms, and the reduction of culturally-specific, ornamental details.

Itten’s Abstractions

While the “unlearning” of received knowledge might suggest an avoidance of art history, Itten actually encouraged students to look at masterpieces with fresh eyes. Using black and white lantern-slide projections or photographic prints, students were asked to discover fundamental compositional elements and unifying shapes. Now, since many of us have access to photocopiers, this is an easy exercise to, ahem, reproduce.

- Make photocopies of the kinds of images Bauhaus students would have studied (e.g. Matthias Grünewald’s Isenheim Altarpiece) OR any images you would like. In my design history class, I have used images of highly ornamented, functional designs (a cradle, a tea pot, an Oriental rug) to reinforce the idea that the Bauhaus ultimately focused on rethinking and simplifying functional objects.

- Ask students to draw over the image, outlining structures and emphasizing straight lines and geometric shapes.

- Extension option: Abstract further by re-drawing some of the outlines and shapes onto a fresh sheet of paper.

Kandinsky’s Questionnaire

Understanding the relationship of color to form was not only crucial to the Bauhaus search for synthesis, it was, essentially, a spiritual quest for Wassily Kandinsky who was one of its most influential instructors. In his preliminary classes, he passed out a simple questionnaire, asking students to fill in each shape with one of the primary colors. Students also wrote down their reasoning for their choices.

- Print out a simple worksheet and pass out markers.

- Or, draw the shapes on the board and have students complete the exercise mentally.

- There’s also an on-line questionnaire produced by the Museum of Modern Art.

- Ask students about the reasoning behind their choices and compare with Kandinsky’s rationale, which was:

- yellow is a “sharp” color that would correspond with the triangle

- red is an “earthbound” color, corresponding with the square

- blue is a “spiritual” color, corresponding with the circle

A majority of Kandinsky’s students made the color/shape associations as he predicted; recent studies, however, have questioned Kandinksy’s methods and findings.

Still, this quick exercise reveals the Bauhaus practice of using subjective/spontaneous/associative methods AND objective/systematic/scientific methods to identify a kind of visual grammar. It is precisely this blend of personal intuition and objective analysis that makes all of the above exercises so rewarding.

As I hope is evident from these examples, I do not want students to merely mimic the Bauhaus style but to learn about the goals and methods of the school by physically engaging in these exercises, much like the Bauhaus students did almost a century ago.

Sources related to Bauhaus pedagogy

Barry Bergdoll and Leah Dickerman, Bauhaus 1919-1933: Workshops for Modernity,

Museum of Modern Art: 2009, exhibition catalogue and website: https://www.moma.org/interactives/exhibitions/2009/bauhaus/Main.html

Website produced by the Bauhaus Centenary Association:

https://www.bauhaus100.de/en/past/teaching/

Johannes Itten, Design and Form: The Basic Course at the Bauhaus (translated by John Maass) Reinhold Pub. Corp: New York: 1964. Jeffrey Saletnik, “Josef Albers, Eva Hesse, and the Imperative of Teaching”:

These are wonderful activities, and such a great approach to teaching the Bauhaus. Thanks for sharing!

[…] stretching session before Johannes Itten’s class. Bauhaus, Weimar. Image credit unknown, via Art History Teaching Resources. Oskar Schlemmer, “Dance de l’espace,” 1927. Image credit 2016 Oskar Schlemmer, Photo Archive […]