On Frida Kahlo, Salma Hayek, and Linda Nochlin: A Classroom Case Study of Art, Gender, and Pain in the Wake of #MeToo

In the wake of #MeToo, many educators pondered how to incorporate the movement into their curriculum. In the spring of 2018, just four months after Ashley Judd’s sexual allegations against Harvey Weinstein sparked a relaunching of Tarana Burke’s original 2006 phrase “Me Too,” I was scheduled to teach an art history course titled “Women and Gender in Art.” As I looked at the loose outline I had prepared for the course a semester earlier, it felt impossible to teach it the way I had been planning, without a direct incorporation of the #MeToo movement.

How could we speak of women and gender in art without addressing the ways in which sexual harassment, sexual misconduct, and sexual aggression has shaped the art world (including Hollywood)? And how could we address a history of art that is often full of imagery that illustrates said aggression towards women? I wondered about how many world renowned paintings and sculptures I had read about or seen as an undergraduate student included only a formal analysis of a rape scene, without any acknowledgement about the violent act of rape itself? (See many artists’ renditions of Susanna and the Elders or the Rape of the Sabine Women.)

I began to consider how I might reshape the class, including direct and indirect nods to the growing #MeToo movement. Using foundational women’s studies texts—such as Linda Nochlin’s 1971 “Why Have There Been No Great Women Artists? and Griselda Pollock’s 1988 “Modernity and the Spaces of Femininity,” as well as traditional art history, film, and media to approach the topic, I focused on the course’s original theme of women and gender, with a contemporary twist.

I took topics that I was already going to cover, such as Frida Kahlo and the way in which she both defied a male-dominated art world, and yet also conformed to the pattern of a female artist having to learn from her father artist, and then I moved such topics in another direction entirely (as you will see in the case study below). I also incorporated #MeToo throughout in smaller iterative ways so that students would not (and could not) forget that this movement was reshaping the way in which we interacted with everything, as a sort of cultural domino effect or boiling point.

For instance, we watched clips of Jill Soloway’s 2016 talk at the Toronto International Film Festival, entitled “The Female Gaze,” and we also discussed Jeffrey Tambor’s then-recent removal from Soloway’s show Transparent as a side conversation, related to but not integral to her work. We talked about works like Paul Joseph Jamin’s Brenn and His Share of the Plunder and discussed how works like this should be addressed with more sensitivity (and attention!) to subject matter (forthcoming abductions, rapes, and “plunder” of the women depicted), rather than focusing solely on formal qualities of the work.

In the following section, I plan to introduce a specific example of class exercises and discussions done with class last year. With my co-author and student from this course, Natalie Madrigal, we reconsider foundational art historical texts, while also exploring experimental teaching techniques and students’ reactions to these pedagogical shifts.

A Case Study of Class Discussions and Exercises

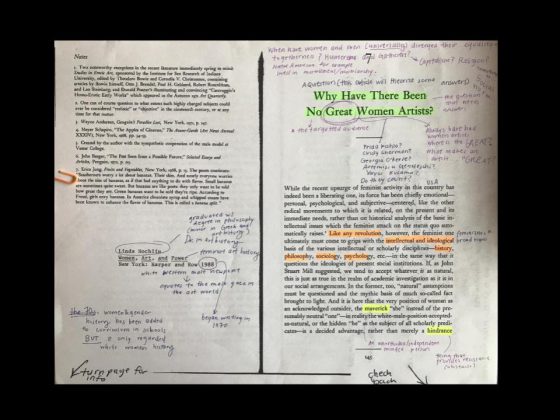

One of the first articles students read was Linda Nochlin’s foundational essay “Why Have There Been No Great Women Artists?” Along with reading Nochlin, I also assigned them an article annotation, wherein they first learned about how to actively read and productively take notes on article and then they demonstrate this gained knowledge by taking notes and submitting their own annotated articles. Despite some complaints about the length and density of such assigned article annotations, students enjoyed this activity overall, often making jokes and astute comments throughout. In an anonymous course evaluation from the end of the semester, 50% of the class cited annotations as being enjoyable, while 88% said that they had gained substantial skills in reading and annotations.

Annotations by Amy Truong, Mt. San Antonio College (See pdf pp. 11-16)

After students completed the Nochlin annotations, we discussed the article in detail during class, first in small groups and then together. I made this handout that contained a number of different activities and questions in order to guide groups through the article’s main topics and structure. By the end, students began summarizing Nochlin’s thesis—that the question posed in the article was incorrect altogether. It isn’t that there haven’t been great female artists, because in fact, there have been some greats throughout history. But Nochlin instead explains “how systemic social, cultural, and political barriers barred women from partaking in the art world in numerous ways. She helped people to understand that it was not that there was an artistic male style or aesthetic that was privileged over some sort of feminine style, but that women had been kept out of the academy, and hence away from art production and the art market itself.”

Our discussions of Nochlin’s argument were active and lively. Students began making independent connections to a variety of topics. Natalie noted that “although women artists faced a lack of recognition and training, this particularly affected women artists of color. If people think there is a small number of women artists in the classical canon, for instance, what does that mean for WoC artists?” The same could also be applied to queer and transgender artists as well. Our class discussed the second wave of feminism that particularly impacted social art history in the ‘60s and ‘70s, noting the prevalence and restrictive application of white feminism at this time. I introduced Kimberlé Crenshaw’s TED Talk “The Urgency of Intersectionality” and students learned the definition and origin of Crenshaw’s term “intersectionality” (a term that many people now recognize, but often misuse). Crenshaw, a civil rights advocate and lawyer, coined the term in 1989 to address the specific intersection of exclusion and oppression at which Black women stood. Intersectionality helps to both name and understand the condition in which people face multiple forms of oppression, such as a queer Vietnamese male immigrant or a disabled Lakota woman, but Crenshaw stresses that each of these people faces very different and specific challenges. Our class discussed how it is necessary to continue expanding the canon of art history to address intersectional oppression through art. Students also began connecting Nochlin’s theory to women actors, producers, and directors in the entertainment industry now. We posed and answered such questions as, How has largely -unreported or- unpunished sexual misconduct systematically and systemically prohibited women from artistic production in film?

We began to build an arsenal of foundational women’s studies essays, opinions, and applications to art history, with further annotations of authors like Judith Butler and bell hooks. About two months into the course, students read about Frida Kahlo, learning not only about her artistic training from her father (which fit one of Nochlin’s discussions about the few famous female artists who were able only able to obtain artistic training through their fathers since art schools would not allow women), but also about how she addresses her ongoing relationship to physical pain and disability in her art and how she defied constrictive gender and sexuality norms ascribed at the time. (This is what Anna Haynes labels the “in-between, “noting that “[t]he cultural locations her [Kahlo’s] artwork explores, between and across the axes of race, sex, gender and sexuality, ‘queer’ the binaries through which differences are normatively mapped.” We took this discussion further too though. In addition to considering Frida Kahlo’s work, life, and training, we also watched portions of the biopic film Frida in class, only after having read Salma Hayek’s op-ed about Harvey Weinstein about the making of the film.

Salma Hayek in Frida, Directed by Julie Taymor, Miramax Films, 2002.

As students watched highlights from Frida, many of which Hayek had detailed in her op-ed, our class discussed Kahlo’s art and Hayek’s film in relation to one another. How did both artists deal with pain in producing their works?, for instance. The class also discussed how scenes from Frida could be analyzed using both Laura Mulvey’s concept of the “male gaze” (in relation to co-producer Harvey Weinstein) and Jill Soloway’s concept of the “female gaze” (in relation to Hayek and director Julie Taymor). Through small groups and a larger class discussion , we drew parallels between Hayek’s struggles, the working atmosphere for women in Hollywood, and Linda Nochlin’s aforementioned essay.

Students also tied in previous readings like Griselda Pollock’s “Modernity and the Spaces of Femininity.” In this, Pollock discusses how female Impressionist painters like Mary Cassatt and Berthe Morisot broke the mold in how they represented women in their paintings, particularly when compared to their male contemporaries. Natalie recalled that Pollock’s article “was geared toward breaking through the ‘spaces’ that are established as appropriate for women in art.” And she applied Pollock’s concept to Frida Kahlo, exploring “how Kahlo’s art was so intimate, that it disregarded the comfort of the viewer and broke through those same kinds of boundaries. This also related to Hayek’s op-ed and her struggle through the creation and completion of Frida.”

Additionally, Natalie incorporated this theme more broadly into the #MeToo movement, noting “how women in the entertainment industry today are adopting that Kahlo-esque disregard for the comfort of the viewers by being open and unafraid to share their experiences of abuse. By creating more content utilizing the ‘female gaze,’ creating more complex characters of all genders, and openly naming abusers and predators who are being protected by the film industry, women in entertainment are utilizing and taking ownership of both Soloway’s concept of the female gaze and Kahlo’s indifference to the viewer’s (dis)comfort.” Hayek’s op-ed is a prime example of this, as are many scenes from Frida, and of course many of Kahlo’s most well-known paintings such as Henry Ford Hospital (1932), A Few Small Nips (1935), and My Birth (1932). All of these display the violence, agony, pain, blood, and loss that can accompany not only miscarriages, but also childbirth. And these were groundbreaking topics to paint during Kahlo’s lifetime.

Lessons Learned: Students and the Professor React

After incorporating the #MeToo movement to my course in a variety of ways, I thought it was important to revisit the topic and analyze student reactions at the end of the semester. Below, Natalie Madrigal recounts her reactions to the Frida Kahlo unit, while also reflecting upon the learning process at large. Next, I share some other anonymous student reactions, while also integrating my own lessons learned from overhauling the course. Natalie recalls:

“I felt taken aback when the topics were introduced in relation to the MeToo movement. Through the duration of my time in college, many of the courses I have taken only very lightly mentioned matters of public contention. Art history classes very rarely stray from their canonical, traditional format. It was refreshing to be encouraged to develop a new point of view and to bring ideas that are foundational to the study of art history into the 21st century, and relating them to issues I find important and relevant to the lives of so many people. Reexamining the lens through which concepts are seen, and applying a modern perspective provides a different and updated understanding of the impact of certain works of art. Through reading and annotating Nochlin, Pollock, and other related articles, I was able to piece together questions and misunderstandings I had in regards to women in art and art history.”

“The use of nontraditional texts, paired with writings that are based in women’s studies (and other disciplines such as sociology and psychology), really completes the historical aspect of art history,in my opinion. These articles serve as a reminder that the way in which history is taught and understood, evolves with time and deserves a newer interpretation. Additionally, although these articles are highly useful in expanding an often restrictive art historical narrative, it is also worth mentioning that there are still lots of perspectives and voices that are not being properly represented—usually that of women of color. The use of current events has broadened the scope through which I, and other students, are able to recognize history in the making.”

Some anonymous student reactions from the end of the semester also referenced this lesson plan on Frida Kahlo and Salma Hayek, with 12% of students mentioning it specifically as a course highpoint.

One student noted, “I loved reading the academic articles and then having in-depth discussions on them in class…. I enjoyed watching the movie Frida and our discussions we had in regards to her as well as Salma Hayek and her experience creating the movie.”

Another said, “I enjoyed the film clips, and watching Frida I would have never seen the movie otherwise and am now a Frida Kahlo fan!”

Another valued the attention paid to Kahlo and varied topics and artists, appreciating “that you showed Frida’s movie. I liked the diversity throughout the course.”

Additionally, when I asked students to rate all of the readings and articles they completed outside of their textbook, every student recommended keeping the readings on Frida Kahlo and only two students suggested removing Salma Hayek’s op-ed. This helped me to quantify students’ reactions to the readings specifically, and to the lesson plan more broadly.

As an instructor, I felt that the practice and exercise of reimagining my course was both powerful and empowering. I saw and heard students discuss an array of personal stories and examples of their own, while also taking complex themes from important texts and applying them to a myriad of art historical examples. Students summarized arguments while also forming their own, feeling empowered to stand on unique footing. Similarly, I felt more motivated to continue to tie together complex themes and contemporaneous events. As students thrived in bringing these distinct topics together, I also succeeded in realizing my endeavor to integrate impactful and contemporary events into innovative materials.

Concluding Takeaways

In taking a cue from the ultimate relevance of the unfolding #MeToo movement last year, I was able to reconsider and assign material in a much more creative way. Because this was not the first time I had felt that contemporary and unignorable social issues (and an accompanying hashtag) should reshape and inform a class redesign, I was ready for the challenge and the additional prep work. In the end, it was well worth it, because it benefited not only my students, but also me as I felt reinvigorated in breathing life into older, foundational (and sometimes more stagnant) materials. My classes bonded over these increasingly relevant discussions and we expanded a foundational, yet restrictive discourse to include more contemporary and intersectional voices and stories.

In considering the far-reaching impact of these larger and more contemporary discussions, Natalie summarized this best:

“Art, much like film, permeates culture so deeply that society can barely recognize the impacts it truly has upon both the following issues themselves and the way we think about them—such as sexual assault, the objectification of women, violence against women, women’s sexuality, and the reinforcement of gender norms and expectations.”

In being ready and willing to discuss and explore the ways in which art and film can impact, conceal, reinforce, or expose such pivotal and pressing social issues, we continue to challenge, trouble, and “difference” an intersectional canon.

This paper inspired a presentation at College Art Association’s 2019 Annual Conference. Resources mentioned in the paper and talk are available here.